Nir pulled into our parking lot in an old BMW with the license plate CHKPKLR—”Check Point killer”—because Check Point was the leader in enterprise security.

Never had a drive to derail an incumbent been so clear!

- Sequoia Capital, on their first meeting with Nir Zuk

CHKPKLR

The conservative nature of Check Point – which may have helped navigating the dot-com bust – was a topic of criticism by one of its first employees, Nir Zuk; The Innovator’s Dilemma hadn’t been published yet in 1994, the year Check Point was founded, which was one year before Clayton Christensen has even published his famous initial article about Disruptive Technologies. In his blog in 2009, Zuk mentioned the Innovator’s Dilemma, and made some bold accusations toward his previous employer – Check Point, who was still the leading firewall vendor at the time:

Why are we still buying firewalls? Because everybody knows they need a firewall and there is no better alternative – or is there? Why are we avoiding innovative technologies? Because we are tired of the appliance fatigue caused by the number of appliances we need to buy, install, manage and support to achieve our network security goals. And why aren’t we demanding more innovation from our firewall vendors? Because we know they cannot innovate – they are big and slow and they haven’t read the Innovator Dilemma. Which basically means that they believe that if they pump R&D money into innovating their stock price will be punished…

So what do we do? As we all need firewalls and none of us want to purchase additional security appliances, my conclusion is: network security innovation must be in the firewall. And the Innovator Dilemma leads me to conclude that a new firewall will come from small and innovative companies. Not from our existing firewall vendors…

More on that later…

Zuk served in engineering and leadership roles in unit 8200 – similar to Shwed’s background – before being offered to join Check Point as an early engineer. In 1997 he relocated to Silicon Valley; while the Israeli management took pride in “keeping their sanity”, Zuk experienced the epicenter of the dot-com boom, and pushed for the company to ride it more aggressively. A category of companies was built selling “firewall-helpers” – appliances that offered additional functionality beyond the core firewall. Zuk – who was meeting and hearing feedback from customers – felt that the Check Point management, back in Israel, was missing the picture by being too conservative, and focused on its unusually high net margins, instead of the market dynamics.

Zuk left Check Point in 1999 and did not experience the bust, a period that in many ways shaped the company; while that was happening, he started a cybersecurity startup and sold it to Netscreen, another Internet security vendor, that was eventually sold to Juniper.

Not bearing the scars of the dot com bust and the global financial crisis of 2008, Zuk has set out to derail Check Point from its leading position; but almost every startup founder is making promises about replacing a more bureaucratic and slower incumbent, yet many end up failing - why should Zuk be able to make his vanity license plate a reality, and become the Check Point Killer?

Disruptive vs. Sustaining Technologies

By now, Disruption Theory has become a victim of its own success, and too many people are using “disruption” to describe any type of technological progress; but back in 2005, the idea was fairly new. Zuk has actually read the books, and as a Sequoia entrepreneur-in-residence, spent the better part of 2005 figuring out how to disrupt the cybersecurity industry.

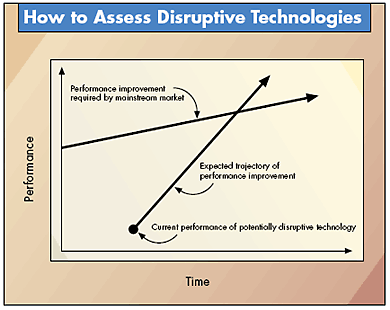

Christensen’s Book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, provided a clear distinction on what defines a new technology as disruptive, as opposed to sustaining innovation:

Most new technologies foster improved product performance. I call these sustaining technologies. Some sustaining technologies can be discontinuous or radical in character, while others are of an incremental nature. What all sustaining technologies have in common is that they improve the performance of established products, along the dimensions of performance that mainstream customers in major markets have historically valued. Most technological advances in a given industry are sustaining in character…

Disruptive technologies bring to a market a very different value proposition than had been available previously. Generally, disruptive technologies underperform established products in mainstream markets. But they have other features that a few fringe (and generally new) customers value. Products based on disruptive technologies are typically cheaper, simpler, smaller, and, frequently, more convenient to use.

Has Zuk found a disruptive angle for network security? Well, that’s what he argued in his blog at the time:

This week Google has announced the Chrome browser. [...] I think the importance of this Chrome browser is what it tells us about Google’s plans for the future – applications will come from the Web and run inside a browser. This is not a new concept – many of the applications that we use today are web-based. Think about Gmail, Salesforce.com, web-based office suites, YouTube, etc. Chrome just makes it clearer – forget about desktop applications, they are something of the past.

There is a slightly more subtle implication, but to me a far more important one. Google and the likes of Google are establishing a direct relationship with the enterprise end user, bypassing the traditional IT department controls over which applications are used and who can use them [...]

The migration of applications from the enterprise data center to Google and Salesforce.com, accompanied by the corresponding shift of information from the data center to the Internet is slowly changing the IT department’s role. It also changes the security risks that need to be resolved [...] So, what can the IT department do about it? [...] At that point, just deal with it. Put controls in place to allow you to determine who can use which application and put security measures in place to protect the use of these applications.

How to do it? Sorry. I cannot promote my company’s products in my blog so I cannot answer this question…

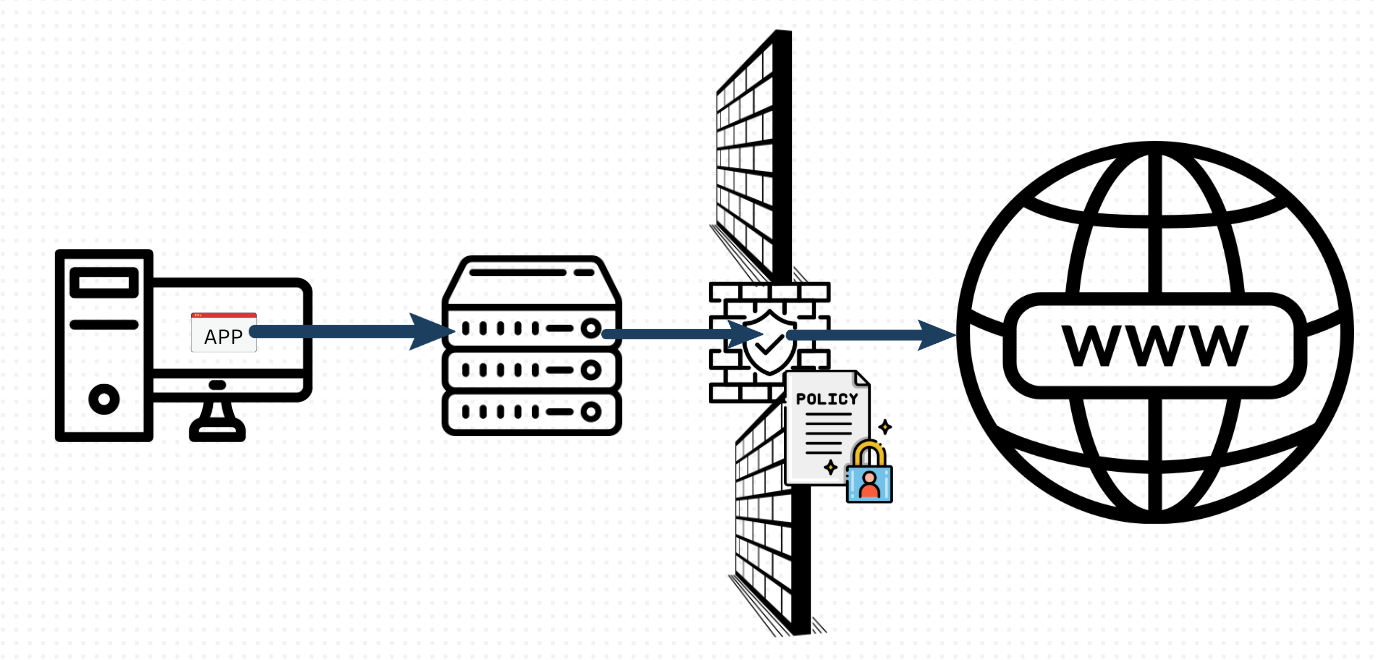

This may sound like ancient history at this point, but before the cloud and the B2B SaaS wave that followed, this is how an enterprise software app like Sybase or Lotus Notes worked: a client (“GUI”) was running on the employee’s desktop computer, working with a backend server that was installed within the company’s premises (usually in the basement, along with many other computer servers). That internal server would connect to the internet – on the client’s behalf – through the company’s firewall gateway; the firewall policy file would contain an allow-list that enables the specific connection, based on the destination IP address. Other connection attempts would be blocked:

The entire paradigm blew up when application clients moved to the browser, and the servers moved off premise:

The main issue here is that a policy file, essentially a list of IP addresses and ports, is meaningless for web HTTP traffic: cloud services don’t have fixed IP addresses, and the port is always 80 for HTTP (and 443 for HTTPS).

Should it be disruptive though? Can’t Check Point evolve its firewall to handle web HTTP traffic, thus making this a sustaining type of progress?

An Incumbent and Disruptive Innovations

In his blog, Zuk was highly confident that Check Point won’t be able to do it:

One of my many roles as a founder and CTO is to meet with customers and talk about their network security issues. These visits are not only informative, they can be humorous as well. For example, on a recent visit to a large, Fortune 500 company, they told me that one of our firewall competitors explained that Stateful inspection would evolve to include application visibility and control. As one of the original engineers working on Stateful inspection, I found this statement extremely humorous.

He went on to explain: Stateful Inspection (see Chart-1 above), the mechanism Zuk had built back in his Check Point days, only inspected the first packet of every TCP/UDP session, and compared it against a policy file; it then either blocked or allowed the entire session, without inspecting any additional packets.

Zuk argued that continuously inspecting IP packets, identifying applications, and dealing with SSL encryption - that would require a completely different system. He called it Next Generation FireWall (NGFW). The NGFW would require much more processing power, and a completely different architecture – one that can construct and analyze the different communication layers.

Palo Alto Networks has launched its NGFW in 2008; Check Point, while not ignoring the need to monitor web applications, took longer to catch up. After I wrote about this disruption story in my Hebrew blog, a former Check Point engineering lead posted the following:

Check Point started investing in what is referred to as NGFW already in 2006, when it acquired NFR for its IPS technology ... other components were still missing, and were developed over the following years: URL filtering, Application Control, Anti-Malware, etc ... but you couldn't sell a real NGFW product without an SSL Inspection engine.

Since most internet traffic is HTTPS, and is encrypted by SSL, it is a critical component, and the one I personally know best - my team built this technology for Check Point's products. We started working back in 2007-08, but there were lots of delays along the way, and we weren't ready before 2010. The first full product came out in 2011.

Check Point wasn’t able to support SSL Inspection – a critical component of securing employees’ access to web applications – until 2011, three years after Palo Alto Networks’ launch of its NGFW. The long delays – likely a result of a need for a fundamentally different architecture – show that Zuk was correct in his original thesis. That’s what created the window of opportunity for Palo Alto Networks to gain a foothold in the market.

A different Business Model

Disruption Theory also explains that in many cases, disruptors develop business models that are very different from the incumbents; that was true for Palo Alto Networks. The company didn’t immediately go directly after replacing the Check Point firewall – a tall order for a startup, which hasn’t established much trust and reputation – but rather by augmenting the traditional firewall at first, with the possibility of replacing its core functionality later down the line. This may seem straightforward in the cloud era, but in the period of point-solutions security applications, this was quite a visionary approach.

From Palo Alto Network’s S-1, filed 2012:

Our Go to Market Strategy

In addition to redesigning the fundamental architecture of the firewall, we have also redesigned the traditional go to market approach in the network security industry

[...] We can target initial sales opportunities as either a firewall replacement or as a replacement of any of the firewall helper technologies. As our end-customers realize the benefits of our platform, we believe that we can accelerate refresh cycles for the existing firewall and its helpers and can replace the core firewall over time

[...] Our architecture enables our end-customers to easily activate additional subscription services without requiring additional hardware, software, or processing resources. This seamless upsell capability offers us significant recurring revenue opportunities from subscription services over time.Building a robust security platform capable of upselling, and expanding through consolidation of adjacent products, has been central to Palo Alto Networks' strategy from its earliest days. The expansion potential explains why the company was willing to aggressively discount initial deals or handsomely incentivize its channel partners – a game Check Point was reluctant to play.

Mechanics of Disruption

So, was Zuk able to derail the incumbent? The answer is yes, according to a billboard that showed up on Ayalon – the freeway crossing through Tel Aviv — in 2013. Positioned next to Check Point’s headquarters, it said “You just passed Check Point. So did we”. This was when Palo Alto Networks received a higher score on Gartner’s Firewall ratings.

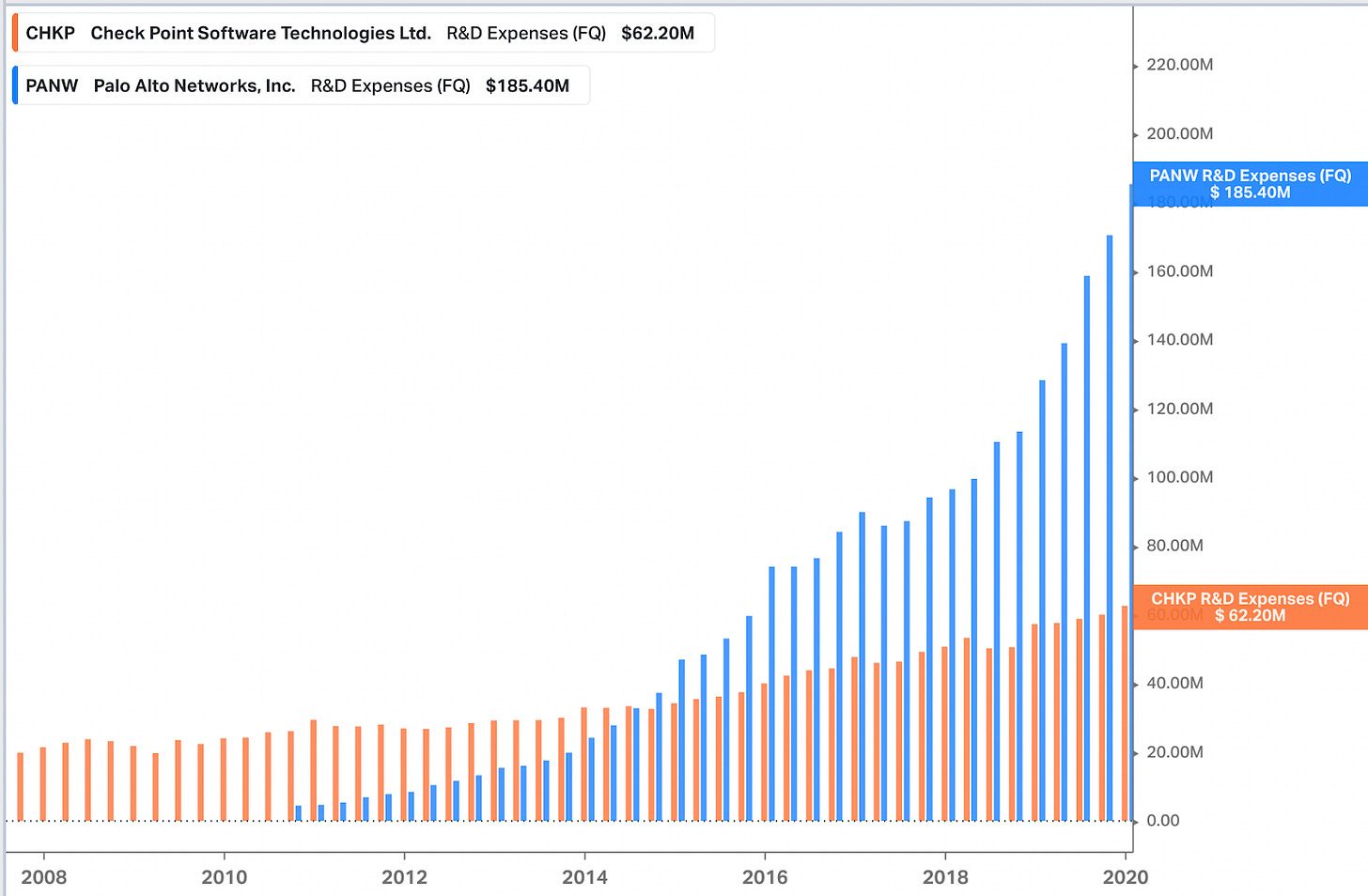

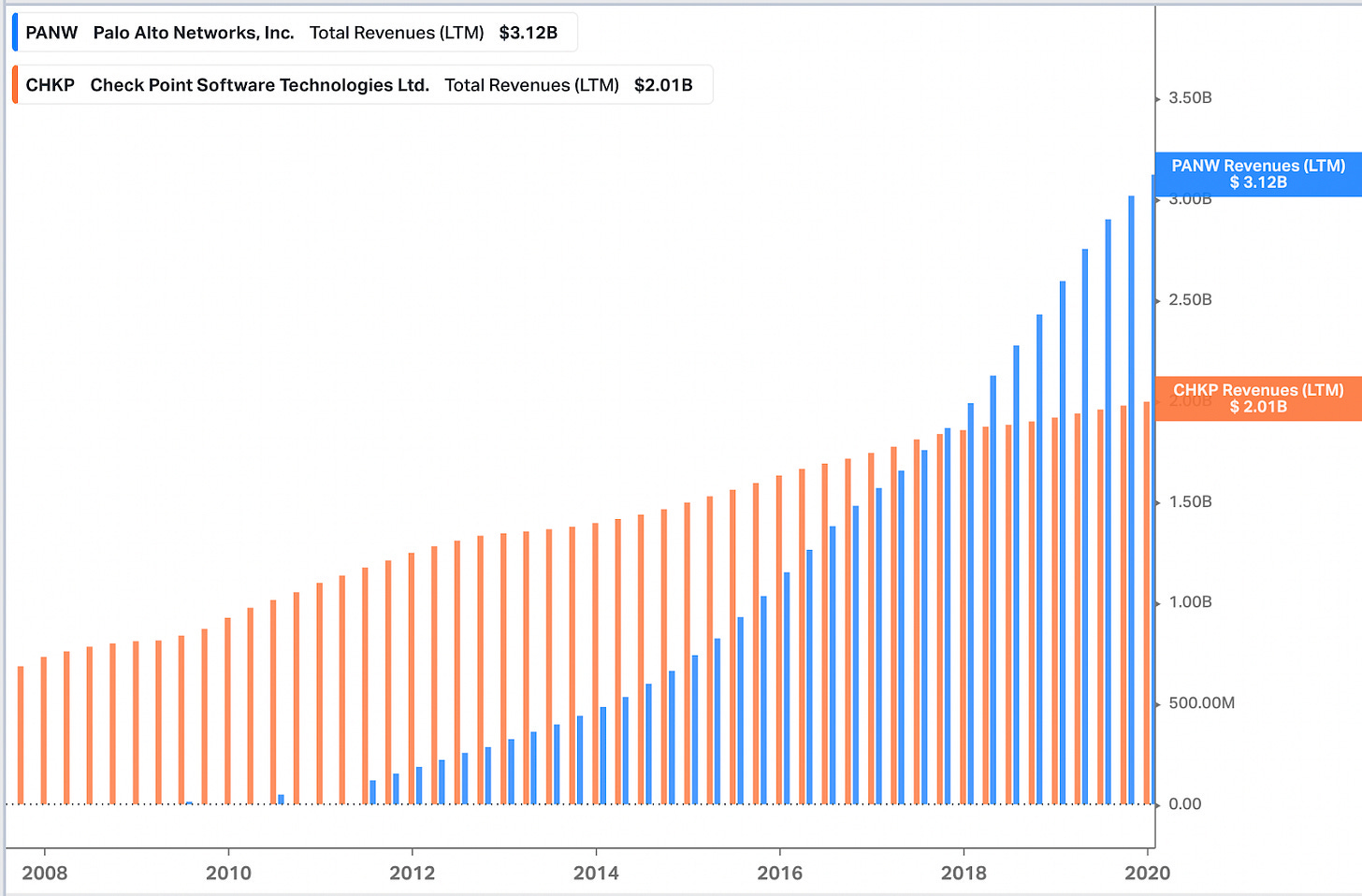

And aside from that marketing ploy, which was a nice closure for Zuk’s old license plate, the numbers tell the same story: Palo Alto Networks’ R&D budget surpassed Check Point’s in 2014, and by 2020 was 3x higher. Revenue followed suit, a few years later.

The graphs are strikingly similar to the classic chart used by Clayton Christensen to explain disruption theory, with the disruptive product starting at a lower point, but ramping up faster.

Disruption Takes Time

The term “disruptive innovation” is misleading when it is used to refer to a product or service at one fixed point, rather than to the evolution of that product or service over time. The first minicomputers were disruptive not merely because they were low-end upstarts when they appeared on the scene, nor because they were later heralded as superior to mainframes in many markets; they were disruptive by virtue of the path they followed from the fringe to the mainstream.

- Clayton Christensen

Note how long it took from the moment Nir Zuk had boldly declared that he was going to disrupt Check Point (in his blog in 2008), until Palo Alto Networks actually surpassed its revenue in 2017: almost a decade. And while everything makes sense in hindsight, the outcome wasn’t clear throughout that decade. Here is Gil Shewd, Check Point’s founder and then-CEO, when asked about Palo Alto Networks going public in 2012:

We are always accused of being too conservative, but I’m happy to be the one who stays in the race, and doesn’t disappear due to being aggressive and careless

[...] Palo Alto is indeed a competitor, but still a niche player. We have far better technology and we have many more customers and installations. They are an aggressive competitor, but I see customers liking our advantages.

I don’t think there is a high chance for Palo Alto to become a success.

Go back to the charts above, and imagine they stopped in 2012 – Palo Alto Networks did seem like a niche player at that point, with a fraction of Check Point’s revenue. It was hard to envision how the revenue trend was going to evolve over time. What was Shwed supposed to do? Drop his financial models and start burning money on a market that did not yet exist, just because somebody insulted him on a billboard? That’s what’s so tricky about disruption.

As Christensen put it, the Innovator’s Dilemma paradox is that the right thing seems like the wrong thing to do, and what seems right is the wrong thing to do.

Another Disruption Story?

I ended the revenue graph above in 2020, because that’s roughly when another adoption cycle – largely induced by Covid – started in the cybersecurity market. And Nir Zuk has been preparing for it - this is how he started his keynote in the company’s 2017 annual conference:

Today I'm going to talk about disruption, about our plans for what's next for the cyber security industry.

11 and a half years ago, in December 2005 I woke up one Monday and I drove up my car … and I stood in front of 10 Venture Partners in that firm and told them how I'm going to disrupt the network security industry. … How I'm going to take on Cisco and Check Point and Juniper and completely change the industry …

Luckily, Sequoia and Greylock saw the vision and decided to invest in Palo Alto Networks and the result as we know today is that we disrupted the network security market. The proof to that is that now we are by far the largest network security vendor in the world by total sales so it's very clear that it disrupted the market.

This morning when I woke up I had a similar feeling to the feeling I had in those Mondays 11 and a half years ago, and the reason for that is that today for the first time I'm going to share with the world, outside of a small group inside Palo Alto Networks, our plans to disrupt the cyber security industry.

This is not the network security industry, this is now the entire cyber security industry. We're going to change it completely and we're going to make sure that no stone remains unturned and the same way that in the network security industry the vendor landscape today looks very different than it was 10 years ago … one of the vendors disappeared the other two vendors are struggling to keep their customer base by offering 95% discounts on their products. The same thing is going to happen to the entire cyber security industry.

What exactly was Zuk’s plan to disrupt the entire Cybersecurity market? How did it work out? And what does it have to do with Wiz? – I’ll leave that story for a different post.

You hooked me with the number plate. I had no knowledge of these intricacies, Matan. The innovate vs disrupt distinction was most interesting to me.