Google's Hope In AI

"Other search companies would have to invest at an equal or greater rate just to catch up. We would launch an arms race and spend our opponents into bankruptcy."

Searching For Profits

In his book, I’m Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59, Douglas Edwards described his initial struggle to develop hope for Google’s chances of building a profitable business (and for his stock options becoming valuable). This is how he described the challenging landscape of internet search in late 1999:

Yahoo's homepage had links to apparel, computers, DVDs, travel, TV listings, weather, games, yellow pages, stock quotes, and chat. It got busier with every passing day. The most prominent feature on the page was Yahoo's hand-built directory with its fourteen major categories from Arts & Humanities to Society & Culture, beneath which were links to all known points in the Dewey decimal system. Buried in the middle of all the text links was a search box powered by our nemesis Inktomi.

Inktomi hadn't always owned that space. AltaVista had provided search to Yahoo until 1998, but they made the fatal mistake of building their own portal site and stealing users from their customer (competing with your own distributor is known as "channel conflict"). Inktomi had no "consumer-facing" search site, so they weren't Yahoo's competitors, which also gave them a clear shot at Microsoft's MSN network and America Online (AOL). Inktomi locked those customers up as well, completing their trifecta of high-traffic Internet sites and ensuring that the state of search across the web was commoditized. You could get any flavor of search you wanted, as long as it was Inktomi. They owned the search market and sat on it as fat and happy as the enormous customers they served.

Other portals wanted a piece of Yahoo's traffic: Excite, Lycos, and Disney's Go.com. And other search companies, like AlltheWeb, Teoma, and HotBot, fought alongside Google for the crumbs falling from Inktomi's table. While Wall Street focused on the portal wars, the struggle for search domination wasn't of much interest to anyone but a handful of analysts. There was no money in it.

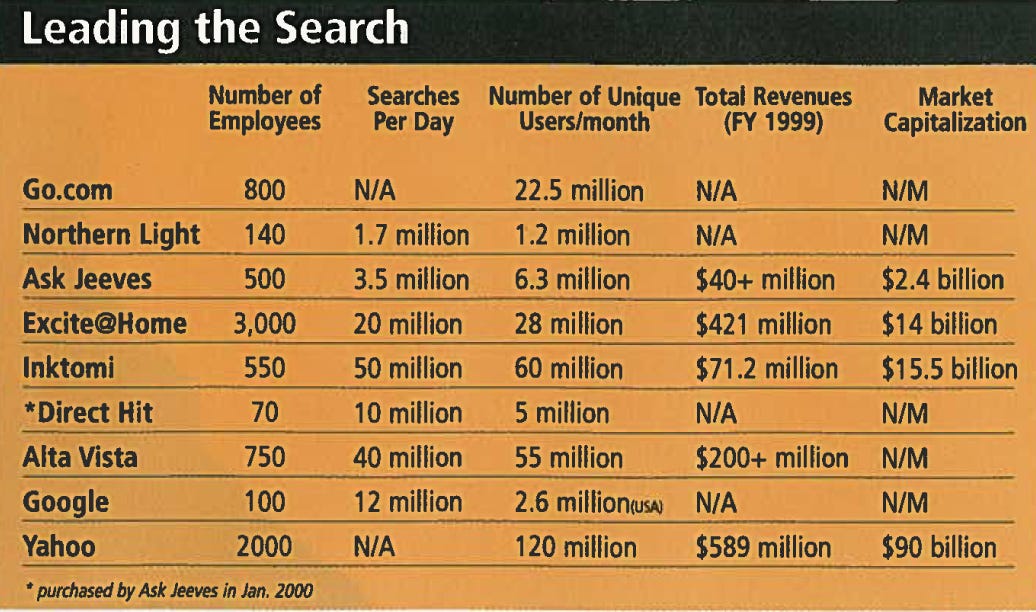

A similar “there’s no money in search” view was presented in the May 2000 edition of Upside, an SF-based magazine for Venture Capitalists (that went bankrupt in 2002). An article, dubbed Searching for Profits, noted that despite Inktomi’s lucrative position as the exclusive search provider for Yahoo, AOL and Microsoft – the three major internet websites at the time – the company was still losing money. It also mentioned how Google was able to draw some traffic through superior technology, but concluded that this was its main (and single) asset. The article ended with the open question of whether “technology leadership would convert at some point into a profitable business”.

The answer, of course, turned out to be an asounding yes. Technology leadership in search ended up converting into one of the most profitable businesses in human history. While it was far from obvious in May of 2000, it is very obvious today, and Aggregation Theory does a fantastic job explaining why that was the case.

What may not be completely obvious, though, is how Google gained its technological superiority in the first place.

Integrated Infrastructure

While the PageRank algorithm – a sophisticated way to determine the importance of a web page, designed by Larry Page during his Stanford PhD years – was the initial breakthrough enabling Google to take off as a superior search engine, it was the first of a long list of innovations. They were a necessity, as the exploding nature of the web pressured Google to index more web pages – more frequently – while responding to more user queries – faster – at the same time. And to do all that while maintaining costs at bay.

I’m Feeling Lucky described a visit to the data-center space Google had rented from Exodus, the world’s largest data center provider circa 2000; in striking contrast to the clean and organized cages of eBay, Yahoo and Inktomi, the space occupied by Google “felt like a shotgun shack blighting a neighborhood of gated mansions. Every square inch was crammed with racks bristling with stripped-down CPUs.”

Google stacked over 1,500 machines; this was 30 times the number of servers its competitor, search-provider Inktomi, has installed in the neighboring cage. Edwards explained:

Google was exploiting a loophole in the laws of co-lo economics. Exodus, like most hosting centers, charged tenants by the square foot. So Inktomi paid the same amount for hosting fifty servers as Google paid for hosting fifteen hundred. And the kicker? Power, which becomes surprisingly expensive when you gulp enough to light a neighborhood, was included in the rent. While renegotiating the lease with Exodus, Jim[, Google’s first sysadmin,] spelled out exactly how much power he needed. Not the eight twenty-amp circuits normally allocated to a cage the size of Google's; he wanted fifty-six.

"You just want that in case there's a spike, right?" asked the Exodus sales rep with a look of surprise. "There's no way you really need that much power for a cage that size."

"No," Jim told him. "I really need all fifty-six to run our machines." It's rumored that at one point Google's power consumption exceeded Exodus's projections fifty times over. It didn't help that Google sometimes started all of its machines at once, which blew circuit breakers left and right until Google instituted five-second delays to keep from burning down the house.

Air-conditioning came standard, too. Again, Exodus based their calculations on a reasonability curve. No reasonable company would cram fifteen hundred micro-blast furnaces into a single cage, because that would require installing a separate A/C unit. Google did. We were a high-maintenance client.

And Google went beyond exploiting loop-holes and opportunities to squeeze its vendors – it also squeezed everything it could from the money it spent on hardware: the use of “commodity hardware” (think: cheap computers that break often), and low-grade RAM due to a global memory shortage, pushed Google to make its software infrastructure extremely fault tolerant.

And here is another story from Edwards:

Larry, Urs, and a couple of other engineers dumped out all the [server] components on a table and took turns arranging the pieces on the corkboard tray like a jigsaw puzzle. Their goal was to squeeze in at least four motherboards per tray. Each tray would then slide into a slot on an eight-foot-tall metal rack. Since servers weren't normally connected to displays, they eliminated space-hogging monitor cards. Good riddance—except that when something died the ops staff had no way to figure out what had gone wrong, because they couldn't attach a monitor to the broken CPU. Well, they could, but they'd have to stick a monitor card in while the machine was live and running, because Larry had removed the switches that turned the machines off.

"Why would you ever want to turn a server off?" he wondered.

I just love this story. Computer hardware is the complement of a web-scale search engine, and Larry Page was modularizing and commoditizing1 his product’s complement using his bare hands.

The server on/off switches weren’t the only thing Google deemed irrelevant; in its quest to up its scale and lower its costs, Google integrated more and more of what traditionally has been sold as standalone IT appliances – networking, security, databases, storage – into its proprietary software infrastructure, through a mind-blowing feat of innovations2, all customized and optimized specifically for Google Search.

The intense focus on Search, and the tightly-integrated approach that became core to Google’s DNA, made it challenging for Google to open up its infrastructure and offer it as a platform. That’s why Google stumbled so much in the cloud era3. But more on that in a different post; for now — just like Google’s infrastructure teams back in the day – I want to remain focused on search.

“Search Is Too Cheap”

Eventually, Edwards grew more optimistic about Google:

Inktomi's contract to supply search results to Yahoo was up for renewal in June 2000, and Yahoo did not intend to extend the partnership … they wanted Google to provide the fall-through search on their site, just as we did for Netscape. If users couldn't find what they wanted in Yahoo's directory, they would use Google to search the web.

Why the shift? Inktomi saw portal search as an unprofitable sideline—they focused on providing search services for the internal networks of large enterprises—so they didn't feel the need to push themselves on Yahoo's behalf. That opened the door for Google.

What underpinned Yahoo’s choice to outsource search on its site, as well as Inktomi’s choice to walk away from the deal, was probably the widespread consensus that viewed search as a commodity. All search engines tasted like chicken. And none of them made any money. The real money was to be made by portals, websites that actually offered content. Content keeps users engaged – and provides opportunities to show them ads – whereas search is just about pushing users away to other websites, thus losing the ability to monetize them.

Google, however, refused to view search as a commodity, given the trajectory of improvements to its technology; the ambitious goal for the Yahoo deal was an index that contains 1 billion websites, constantly being refreshed and re-crawled.

Through innovative infrastructure engineering, Google’s cost per query went down so much that Larry Page started saying “Search is too cheap”. I’m Feeling Lucky explains:

Spending money to improve search quality would create a perceptible gap between Google's results and those of our competitors, enabling us to build a brand based on quality. Other search companies would have to invest at an equal or greater rate just to catch up. We would launch an arms race and spend our opponents into bankruptcy. "Raising the cost of search will in fact increase the profit," Urs believed. "Your top line is going to go up much faster than your bottom line, and your margin is really very large."

Larry and Sergey wanted a focus on efficiency, but they also wanted to find out how much better Google could get if we threw twice as many machines at the problem of search quality. So they tried an experiment.

"In 2001," Sanjay recalls, "I was sitting in Larry's office and he just said, 'Here are three thousand machines. You guys figure out something to do with that.'“

It’s incredibly hard, during times of great technological shifts, to predict how value chains4] would end up organizing; Yahoo assumed search was a commodity (as did everyone else), and tried to build a sustainable business by integrating as much content as it could alongside its websites directory. In assuming search was already good-enough – and that users wouldn’t care if AltaVista was swapped with Inktomi or Google – Yahoo failed to envision how large the internet may become; the explosion of websites rendered the content itself a commodity, and the ability to search and discover said content turned into the critical component of the value chain that’s never good-enough, and where the value ended up accruing. Google was able to capture this value by integrating an index of the entire internet, alongside the IT stack required to power it, and the best algorithms to search through it.

By the time Yahoo realized their mistake, and tried to build their own search through acquiring Inktomi in late 2002 – Google was already way ahead.

Google’s Hope in AI

This story has obvious parallels to the evolving dynamics around AI: the current consensus is that Large Language Models are a commodity, and the ongoing race is to incorporate them into a winning product. How would you handicap Google’s chances in a race like that? While I can’t recall a single case of Google winning through having a better polished consumer-product, I can think of many product categories where Google tried and failed to gain meaningful traction. Google Plus probably still remains the key symbol for the latter. (not trying to offend anyone; I personally worked on failed-to-gain-traction products myself during my years at Google).

But some Google products do succeed big time: think of Gmail, which just celebrated 21 years since launched on April Fools Day of 2004. It seemed like a great prank; no way Google is offering unlimited storage for your inbox for free. Gmail never offered an outstanding user experience, but that was fine; it won due to superior high-scale infrastructure and a big-data flywheel (e.g. the more emails running through Google, the better its spam filtering). Oh, and by the way – after a major multi-year investment – Google shut down its attempt to build a superior email client. Gmail has been improving, but my point is that building sleek products was never Google’s advantage.

The skepticism around Google and AI is understandable: in contrast to Google’s complete dominance of search, Gemini is perceived as yet-another AI chatbot. And why should Google’s AI app fare any better than did its social network or instant messaging or payments or music streaming apps?

What if it turns out, though, that the current consensus is wrong, and AI models aren’t a commodity? Just like search in 2000, perhaps AI technology can get so much better – and faster and cheaper – that it would be possible to develop a significant and durable technological advantage? It could be that the answer is no, but Google’s biggest hope in AI – at least when it comes to the consumer space – is that, again, “technology leadership would convert at some point into a profitable business”.

Google’s AI strategy is strikingly similar to the one that made its search engine so successful: tight integration across the stack – from hardware to data to models to cloud infrastructure to consumer apps; everything is proprietary, developed (and optimized) by Google5. This doesn’t guarantee success, but this is Google’s best shot at leveraging its core advantages.

One key question is whether Google’s integrated infrastructure leads to significantly lower inference costs, warranting a “AI is too cheap” mentality. The arms race is already underway in AI, as large tech companies rush to one-up their spend on GPUs and data centers. If Google enjoys a better bang for its buck when it comes to serving AI queries – compared to OpenAI usage of NVIDIA GPUs hosted by Microsoft – then Google should be spending as many as it can on distributing AI; a real advantage on cost would make it such that other players would have to significantly outspend Google just to stay in the game. Perhaps this is already happening, as @sundarpichai posted on X (on April 1st, Gmail’s 21st launch anniversary):

Gemini 2.5 shot right to the top of the benchmark tables (for now at least). And it’s widely available for free! But while a similar strategy worked in Google’s favor 25 years ago, time will tell if Google gets lucky in this case too, or if we’ll just see competitive models soon being launched (and priced competitively) by other AI companies. While it may take time for the dust to settle on whether betting on an integrated infrastructure again leads to superior technology and a durable advantage, it is Google’s best hope; so it might as well, as Sundar put it: Give it a try!

This is a reference to Joel Spolsky’s famous law of tech, Smart companies try to commoditize their products’ complements.

BigTable, MapReduce, Google File System and Software-Defined Networking, to name a few.

See the famous Stevie’s Google Platform Rant, though Google Cloud is doing better now.

This analysis is based on the law of Conservation Of Attractive Profits, as described in chapter 6 of The Innovator’s Solution by Clayton Christensen.

Though unlike with search, not solely focused on serving Gemini. There is a degree of modularity aimed at serving Google Cloud customers as well as Google first-party apps

Great analysis. I broadly agree with Google's strong positioning due to its infrastructure, data, and product surfaces

One additional angle worth considering is the accelerating impact of open-source models

If foundational model quality commoditizes faster than expected (similar to how Kubernetes reshaped cloud competition), the key battleground could shift from model performance to product integration and distribution much sooner than the historical search analogy suggests

Wrote some thoughts on this dynamic https://www.tiroshi.com/blog/googles_ai_strategy_vs_open_source/ - would love your take if you have time

Thanks for sharing. insightful