Internet Portals And Ridesharing Apps

How Google Search beat internet portals, and potential lessons for the future of autonomous vehicles and robotaxis

Uber and Waymo

From Bloomberg:

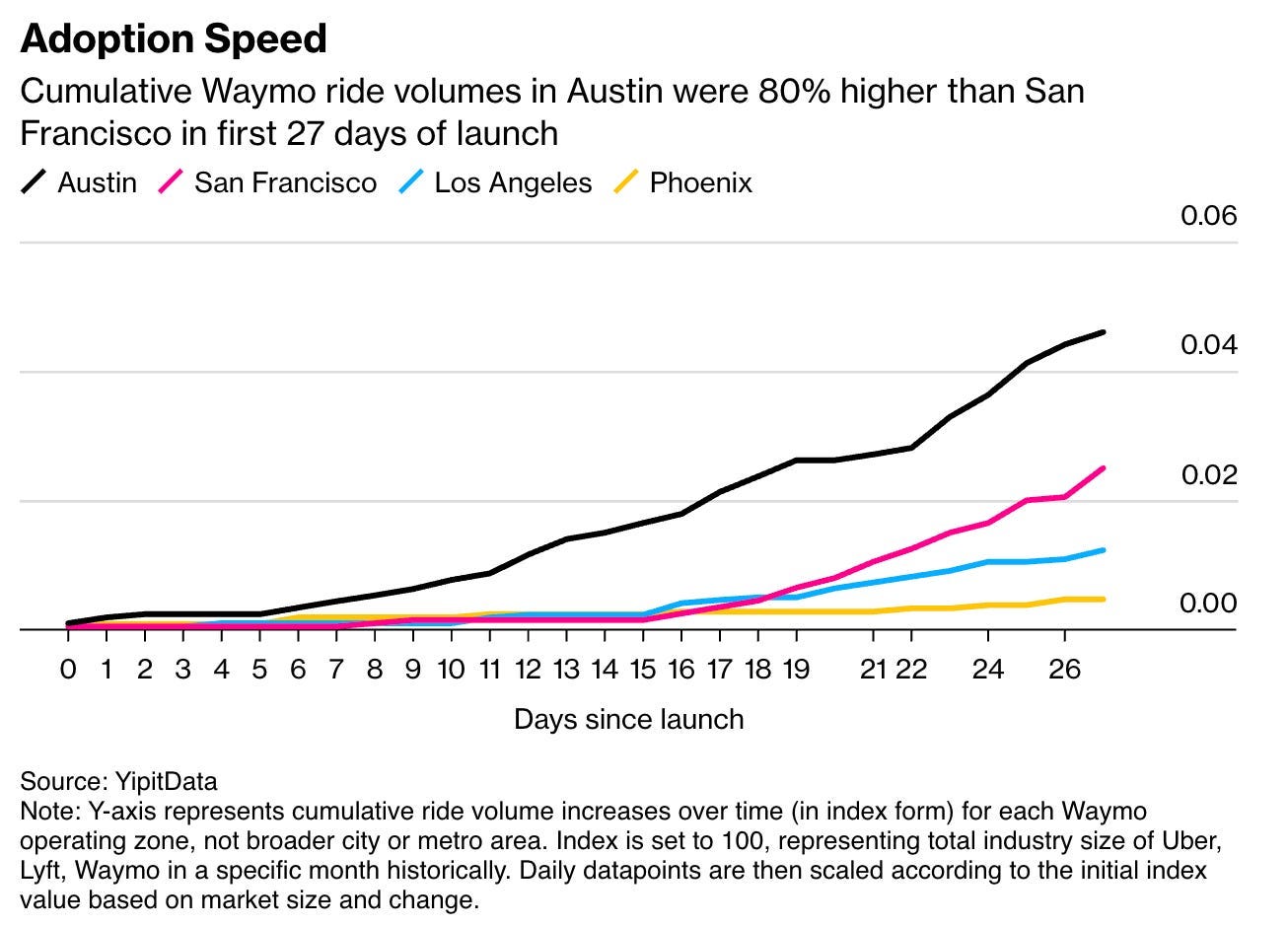

Waymo robotaxis made up about 20% of rides offered by Uber Technologies Inc. in Austin in the last week of March, underscoring how consumers have warmed to the autonomous service since the companies launched a partnership early last month.

… [YipitData] found that Waymo, Alphabet Inc.’s autonomous vehicle unit, has racked up 80% more driverless rides in its operating zone in Austin in the first 27 days of offering service than it did in the early days of its San Francisco launch. A key difference in the rollout is that Waymo trips are exclusively available through Uber in Austin, while in San Francisco they’re available only through Waymo’s own app.

What’s interesting is that the distribution power of the Uber app is likely a major driver of Waymo’s incredibly rapid adoption rate in Austin. Much faster compared to San Francisco, where people are generally open to trying new things, but couldn’t try Alphabet’s robotaxi via their already-installed Uber app; in SF, Waymo rolled out its robotaxi service via a dedicated Waymo app1.

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi has highlighted this strength – Uber’s aggregation of ridesharing demand – in an interview with Ben Thompson last February:

Ben Thompson: … in the short term, if it’s a Tesla or it’s a Waymo, they have to build out these fleets to even gain baseline capacity, much less even attempt to reach into higher demand areas. It’s all fixed costs, it needs high utilization, which drives them into your arms because you have the most customers, you have the cheapest customer acquisition, all these advantages that you’ve talked about.

But, if suddenly they can develop the wherewithal to stomach losses for, I don’t know, I mean the Waymo share in San Francisco seems pretty solid right now where they’re not necessarily being fiscally disciplined, is that a real risk factor for you?

Dara Khosrowshahi: Listen, if you don’t care about economics, then business model logic, that doesn’t matter, but at some point you need economics to work in order to scale, and in a world where certainly if the cost of capital is high and these cars are relatively expensive, the player that’s able to drive the highest utilization of these vehicles is going to have the lowest cost of capital.

The player who works with us is going to be able to expand into every single market very, very quickly, will be first to market and being first to market matters, and I think those two elements, which is lowest cost of capital, ability to scale fastest, are going to play to the advantage that we bring in terms of being the best partner for AV in the world.

So we’re pretty confident of our position.

The early data from Austin supports this last sentence2. I can’t ignore, however, the resemblance between the Uber-Waymo relationship and the relationship Yahoo had with Google in the early 2000’s. A replay of that story might undermine the confidence Khosrowshahi is expressing.

Disrupting Internet Portals

I have this great quote from a search engine, which is now actually out of business … when they were just becoming a portal, [the CEO] said “our search engine is 80% as good as the other guys”.

‘In fact,’ he said ‘we've done focus groups, we've done all this research, and we don't think the quality of search matters, because people can't tell the difference’

[...] It's interesting, the leaders of these companies didn't understand that search technology would improve. They thought that search was done, and that they should move on to other things like horoscopes or whatever.

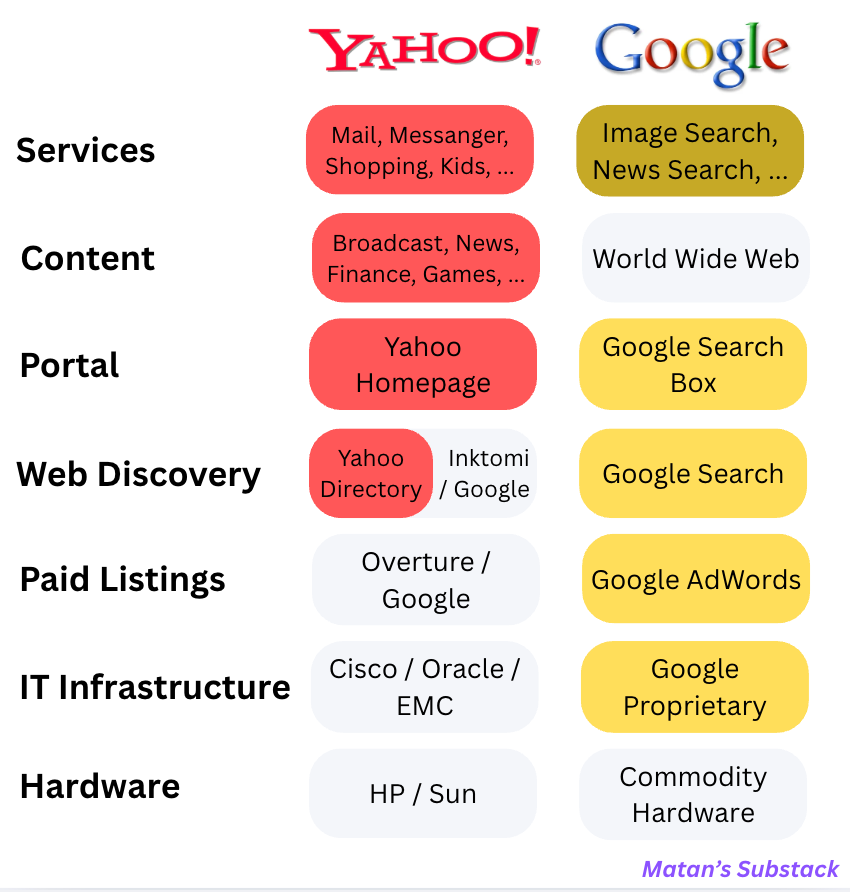

Yahoo started as a directory of web-links (“Jerry and David's Guide to the World Wide Web”), maintained by a team of Surfers – human crawlers and indexers, essentially – responsible for discovering new websites and cataloging each of them under a relevant category. In its announcement of the deal with Google (June 2000), Yahoo explained that “Google will provide its underlying Web search engine to serve as a complement to Yahoo!'s popular Web directory”.

Through its superior infrastructure, Google was able to build a constantly improving search engine that eventually rendered Yahoo obsolete (see: Google’s Hope In AI); and it didn’t stop at search: the fundamentally different architecture, built for web-scale, turned out useful for building a superior advertising product as well.

Overture, the leading engine of search advertising, was gaining ground thanks to its innovative Cost-Per-Click model: the higher the bid made by an advertiser, the higher placement the ad received. It was up to the user to click-click-click through a bunch of irrelevant ads, and potentially click on one of them. Only then would Overture make any money (and share the revenue with the hosting portal). Google further improved on this model, by ranking ads based both on the bid AND its relevance. It wasn’t simply about how much the advertiser was willing to pay; it was also about the quality score of the ad, in the context of the particular search query. In order to estimate the latter – quality score for an ad, given a search query – Google could initially leverage its search ranking algorithms, and create a flywheel that collects additional signals and incorporates them into the ad ranking algorithm3.

Google also found the integrated approach useful to move up the product stack: when Gmail launched in 2004, webmail products – offered by almost any portal or ISP – were considered a commodity: few megabytes of storage, annoying banner ads, and inability to search through older messages. That’s what made it so hard to believe that Gmail free 1GB offering was real.

While Yahoo employed human editors to manually curate articles, from a limited set of publications, for its News product, the Google News pages were generated automatically. Aggregating 4,000 news sources when launched, Google News scaled much better across countries, languages, and topics.

Similarly, Google’s automated product search (initially named Froogle) scaled better compared to Yahoo! Shopping.

You can see where I’m driving with this.

And while Yahoo was adding content and services (“horoscopes and whatever”) to its portal, in an attempt to engage users and show them banner ads – Google simply allowed them to search for [horoscopes]. Even the astrology-seeking traffic was better monetized by Google: either through search ads – horoscope websites bidding for traffic from Google Search – or through AdSense. That was another advertising product by Google, that embedded ads on websites across the internet. AdSense was another manifestation of Google’s infrastructure advantage: every web page was already analyzed by the search index, and Google had the best signals to determine the most relevant ads to display.

The key takeaway is that Google’s integrated infrastructure allowed it to create products with zero-marginal supply cost and unlimited scale; given Yahoo’s reliance on manual editing and curation, which had real costs, and set limits on scale – Google’s victory seems inevitable in hindsight.

There was another challenge, however: it’s not enough to simply build an infrastructure with the potential to outperform incumbent internet portals; it has to be kick-started with a huge volume of traffic and expanded with large amounts of capital investments.

Yahoo, AOL and Google

When Yahoo dropped Inktomi as its search vendor in favor of Google – in the spring of 2000 – the Yahoo homepage saw 48.6 million unique visitors, second only to AOL. Google, meanwhile, had slightly over three million, and didn’t even make it to the top-100. It seemed reasonable to outsource search to Google, and focus on differentiated content and services, such as Yahoo! Mail, Finance, Broadcast, or Shopping (“things like horoscopes or whatever”, as Page mockingly referenced it4).

Yahoo didn’t willy-nilly hand over its search box; the Google founders had to offer favorable financial terms in order to win the deal, including millions of stock warrants. Trust was established based on the companies originating from the same place – the Stanford campus – and sharing a board member: Mike Moritz of Sequoia Capital.

While Yahoo could play its search vendors against each other, Google really needed Yahoo at that point: yes, the integrated approach would prove to be superior, but it was also going to take huge volumes of search traffic, and large amounts of capital investments, in order to get there. Both could be gained by partnering with Yahoo.

Yahoo’s upper-hand allowed it to choose Overture, in November 2001, to power ads targeted to search keywords. A major blow for Google. Yahoo was still going to pay Google for search results, but – perhaps as a hedge – would not monetize them through Google AdWords, but rather through another company. Overture. As Doug Edwards tells it in his book I’m Feeling Lucky, Google’s founders – who believed they had a better product – were furious, but were careful not to bad-mouth Overture and risk upsetting Yahoo, their biggest strategic partner.

Another Overture customer, and the biggest internet portal of the time – AOL – was willing to consider Google AdWords, knowing they had the leverage; I’m Feeling Lucky describes:

Before Google entered the syndication market, Overture had owned a near monopoly. They set the terms for partners on revenue splits. For small partners the split might have been fifty-fifty, but for a large partner like AOL it would have been more generous. AOL might have been taking seventy percent of the revenue when someone clicked an Overture-supplied ad on their site. Already, though, as George Mannes had postulated in his article, Overture's margins were slipping downhill. Our negotiating team gave them a helpful shove. We were willing to offer AOL eighty percent, a number we could afford because we kept all of the revenue for ads on Google.com

AOL noted our strategic goals and our generous gesture and demanded ninety-one percent. "We're going to make your network," AOL told Alan's team.

"No, you're not," Alan responded. Everybody knew he was bluffing. Larry and Sergey were desperate to kick-start our ad-syndication program, and a deal with AOL would leap across the Internet, creating a network effect that would bring in thousands of other sites.

Probably seemed like a great deal for AOL at the time, but what a bargain for Google it was in hindsight; the AOL user base was effectively being handed over, and instead of paying for this privilege, Google was able to make a little money in the process of acquiring them.

The interesting takeaway is that partnering with portals such as Yahoo and AOL – the destination websites which controlled the most traffic, or aggregated demand if you will – was critical for Google initially, in order to reach escape velocity.

Lessons From History

Not to over-index on single historical case, this story does carry a clear warning for Uber: the advantage it holds in the short term – a quick way for robotaxis to scale in new geographies – might not protect it in the long term. Similar to how Google’s Search and Ads products were desperate for traffic from AOL and Yahoo initially – Waymo might benefit from Uber’s existing user base for a while, until it would no longer need it.

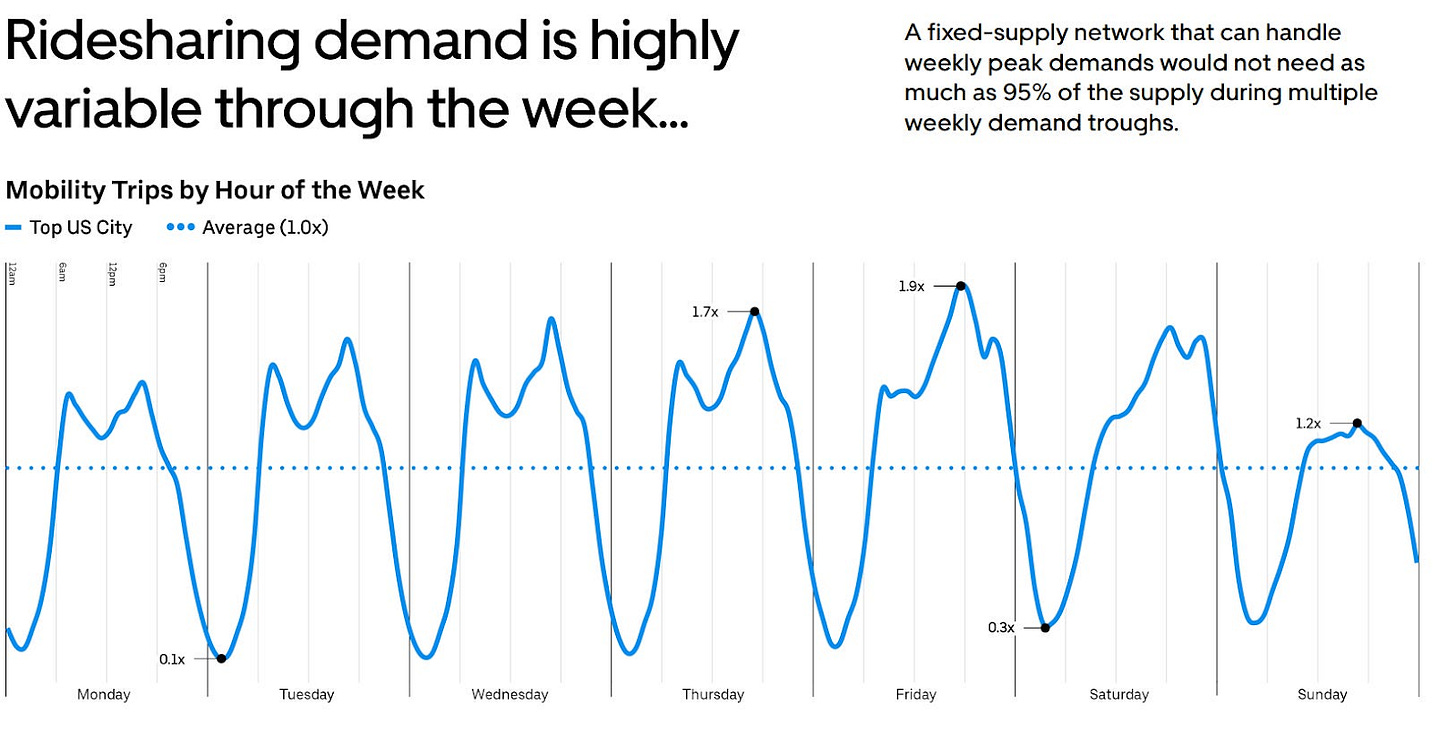

Another point in Uber’s favor, mentioned by

in State of Rideshare and Autonomous Vehicles, is the huge variance in ridesharing demand throughout different hours of the day. This may lead to a hybrid equilibrium of robotaxis complemented by human drivers: robotaxi capacity would be built to roughly satisfy the average level of demand, thus keeping a mostly high level of utilization. Human drivers would augment it during peak hours.Uber CEO explained while presenting at a Morgan Stanley conference in early March:

…you see demand not only to be highly variable on a seasonal basis but a day-to-day basis as well. So we think a hybrid market of humans and AV players on a market-to-market basis is going to be the best kind of path forward for the next 10 to 15 years.

The counter argument would be that Yahoo, too, viewed Google Search as a way to complement its human-curated web directory. As the Larry Page quote above explains, nobody anticipated how much cheaper, and better, search quality could get. Could history repeat itself when it comes to improving the economics of autonomous vehicles and the quality of their driving?

While it is dicey to force a single analogy into predictions about the future, the same can be said about leaning too heavily on demand patterns shaped by the existing cost structure. If Waymo could significantly reduce the cost of building and maintaining its vehicles (that’s a big IF!), couldn’t they find other ways to utilize an array of self-driving robots ready to move around town at close-to-zero marginal cost? Packages could be delivered from warehouses to stores, for example, during the 3 a.m. ridesharing through.

There is a key difference, however: Google was able to overthrow the internet portals within a few short years thanks to the frictionless and unregulated nature of bits on the world wide web. Things take much more time when it comes to the heavily-regulated, high-friction challenge of moving atoms around in the physical world.

It’s always hard to predict the pace of improvement for new technologies. It has been a long journey since Google first revealed its self-driving car project in 2010. And it may very well be the case that human drivers would still be holding the wheel – at least for a fraction of rides – in another fifteen years from now; it’s also possible, however, that at some point during this period, driving for Uber would become the equivalent of the Surfer gig at Yahoo.

This isn’t the only reason that Waymo ramped up faster in Austin: in SF it was competing with GM’s Cruise (that have since shut down its service) and now with Amazon’s Zoox.

Of course with the disclaimer that it might be foolish to extrapolate based on just 27 days, and that we have yet to see the impact of the supposedly-coming launch of Tesla’s robotaxi in the city.

Overture filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Google over the CPC model, which was eventually settled months ahead of Google’s IPO in 2004, after Yahoo had acquired Overture.

Yahoo’s horoscope page is still up and running as of April 2025.