Oracle, Amazon, and the Winner's Curse

How Oracle Missed The Cloud, And What Amazon Might Be Missing With AI

Amazon’s potential AI risk is one fascinating insight raised by a brilliant article from Ben Thompson recently, Paradigm Shifts and the Winner's Curse. The entire piece is a spectacular blend of tech history, macro-trends, and company-specific strategic analysis, and is a delightful read. I recommend the whole thing (I have read it twice, and intend to reread it again in the future).

One interesting thing that stood out to me about Amazon was that it might be repeating the very same strategic mistakes – made by the incumbents of the pre-internet era – which enabled the rise of AWS to cloud dominance.

Warren Buffett’s Secret Investment That Failed

Wait a second, IBM is a tech company, and you don’t buy tech companies. Why have you been buying IBM?

That was Becky Quick’s first reaction, after Buffett revealed – in a November 2014 interview with CNBC – what was the stock he had been secretly buying over the previous months. Buffett bought $10.7B worth of IBM shares; this might not sound like a lot of money today, but at the time this amounted to 15% of Berkshire Hathaway’s stock portfolio.

To the puzzled interviewers, Buffett explained:

… I’ve probably read the annual report of IBM every year for 50 years. And this year it came in on a Saturday, and I read it. And I got a different slant on it, which I then proceeded to do some checking out of. But I just—I read it through a different lens. [...] just like I did with the railroads [...]

I don’t think there’s any company that’s done a better job of laying out where they’re going to go and then having gone there. They have laid out a road map and I should have paid more attention to it five years ago where they were going to go in five years ending in 2010. Now they’ve laid out another road map for 2015. They’ve done an incredible job.

First, Lou Gerstner, when he came in, he saved the company from bankruptcy. I read his book a second time, actually, after I read the annual report. You know, “Who Said Elephants Can’t Dance?” I read it when it first came out and then I went back and reread it.

And then we went around to all of our companies to see how their IT departments functioned and why they made the decisions they made. And I just came away with a different view of the position that IBM holds within IT departments and why they hold it and the stickiness and a whole bunch of things.

To sum up: IT departments were strongly dependent on IBM for their on-premise infrastructure. Buffett’s insight was based on things like the economics of this business, the quality of management, the competitive position. Just like he never needed to understand how a diesel engine works in order to successfully invest in railroad companies – it didn’t require an understanding of how storage servers or database management systems worked, in order for Buffett to invest in IBM in 2011. Except that, you know, maybe it did.

Fast forward six years, Buffett sold out of IBM. The investment didn’t work. To CNBC he explained:

If you look back at what they were projecting and how they thought the business would develop I would say what they’ve run into is some pretty tough competitors

Isn’t that interesting; what happened to the “sticky and strong position within IT departments”? Why couldn’t it protect IBM against “tough competitors”?

Larry Ellison’s Grand Plan

And who were those “tough competitors”? Perhaps Larry Ellison, who in the early 2000s was determined to take over the software world. From the book Softwar:

The internet model of computing has given birth to the utility model of computing and software as a service. We couldn't be better positioned. Our fault-tolerant grids of Linux database servers provide the ideal low-cost, high performance infrastructure for utility computing. Our applications outsourcing is one of the largest examples of software as a service in the industry. I know it won't be easy to catch Microsoft. They are more than three times bigger than we are, but they make money on desktop computing—Windows and Office. They are nowhere in utility computing. SAP is nowhere in utility computing. IBM is advertising utility computing but delivering labor intensive custom systems. So if utility computing is the future, then the future is ours.

Ellison was correct about IBM – their dominant position as integrators of on-premise IT systems, was not going to translate into a leading position in the age of cloud. He turned out to be incorrect, however, in assuming that Oracle’s dominance in the on-premise paradigm would translate into dominance in what he called “utility computing” (an earlier name for “cloud computing”.) Thompson’s article shows a similar case with Microsoft and Nokia, who dominated the pre-smartphone era, but failed in smartphones.

What did he get wrong? Well, examine his arguments: Oracle has the best database servers and the best enterprise applications. All that’s needed is to install them in a data center managed by Oracle, and sell them as a service over the internet.

The concept wasn’t new for Ellison; in 1996 he was promoting a Network Computer (NC), a lightweight device that’s connected to backend servers through the internet. The NC software would come from Oracle. Andy Grove mentioned it in his book, Only The Paranoid Survive, as a potential threat to Intel’s dominant x86 architecture; Grove concluded, however, that the internet infrastructure circa 1996 could not support the NC concept – which meant Intel was fine! – but that it should be under ongoing monitoring. Too bad Intel’s management didn’t listen, since this exact threat finally materialized a decade later with the release of the iPhone in 2007. The apps were indeed connected to backend “utility” servers; these servers weren’t, however, running Oracle software.

Oracle and the Winner’s Curse

In The Winner’s Curse, Thompson describes how Microsoft lost mobile not because it ignored it – quite the opposite, they first launched Windows Mobile as early as 2000! – but rather because they assumed that the Windows platform, which dominated the previous PC paradigm, could extend to mobile. So they launched a miniaturized version of Windows (with a Start button!) running on a handheld-device.

Similarly, Oracle didn’t ignore the cloud, but rather pursued it – aggressively – with the wrong strategy. Oracle assumed that the dominance of its database – powering the vast majority of enterprise applications of the on-premise IT era – would extend to the cloud.

Mobile ended up requiring a fundamentally different architecture, however, redesigned from the ground up – such as the ARM foundation or touch-based interactions – which Microsoft just didn’t pursue.

Similarly, the cloud ended up requiring a fundamentally different architecture from the ground up; Amazon Web Services, which started by renting out the most basic primitives – storage and compute – was best positioned to redesign from scratch, in a way that was optimized for the new paradigm.

In the early 2000s Oracle and IBM focused on promoting their Java Enterprise Edition (J2EE) offerings; those were high-value-add software systems, at the very top of the stack that dominated the on-premise paradigm. At the same time, Amazon Web Services enabled a new era of software engineering: agile development, which was based on completely different assumptions. In stark contrast to the huge upfront design effort required by the endless configuration files of Oracle Application Server, cloud-based startups had constant access to modifying their system. AWS was initially mocked as an insignificant storage-rental service for startups, but the Lean Startup founders of the mobile era influenced the way AWS was designed: meant for continuous deployment and quick iterations. Something that the Oracle Application Server – built for an era of “finalized fully tested” software products – could not offer.

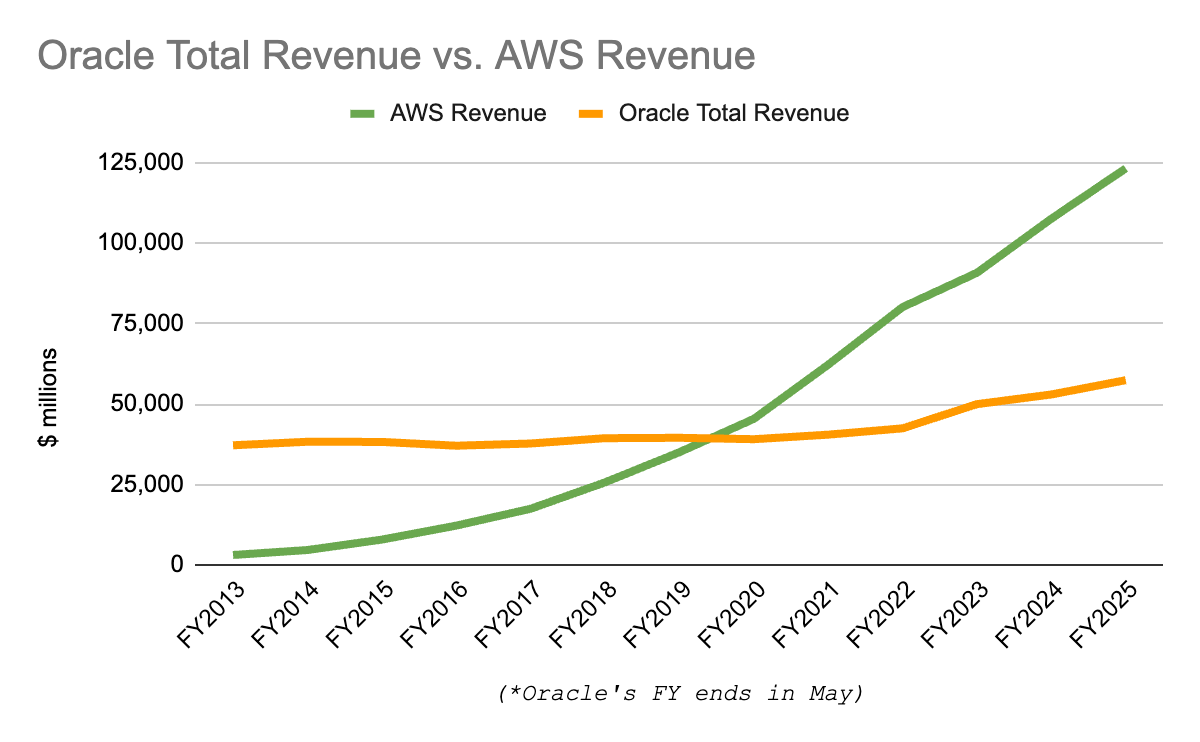

Winning over the backend servers powering the apps of the mobile era gave AWS the scale to continuously spin the efficiency flywheel, continuously lowering its operating costs, and creating a structural cost advantage that Oracle could never catch up with (see this deep dive from

on Amazon’s custom infrastructure).A pay-as-you-go flexible database was architected differently than one meant to run on a single expensive machine that never fails; Oracle Database was the latter, but software developers just wanted their database to grow alongside their user base. RDS, Amazon’s Relational Database, excelled at just that, even if it wasn’t on par with the advanced capabilities of Oracle Database at the time.

The cloud also gave rise to the NoSQL movement; While databases such as MongoDB were initially mocked by Oracle DB experts for not adhering to ACID properties, web developers loved the flexibility of not having to design your entire data schema upfront, or going through the painful (and often, scary) process of changing the schema. It was far better at the things that mattered in the agile development era. That’s a textbook example of the “Innovator’s Dilemma”. Also, MongoDB became far more robust and secure over time.

It took a while for Ellison to fathom all of this; somewhat parallel to Steve Ballmer laughing at the iPhone in 2007, Ellison was mocking the cloud in 2009:

… My objection is the absurdity. it's not that I don't like the idea. What is, I mean it's this nonsense. Uh, I mean the guy says, oh it's in the cloud. Well what is that then?

You say, are we dead? Oh yeah. We're dead. If there's no hardware or software in the cloud we are so screwed. But it's not water vapor. All it is is a computer attached to a network. What are you talking about?!?

I mean what do you think Google runs on? I'll ask you. They run on water vapor?!? I mean Cloud. it's databases, and operating systems, and memory and microprocessors, and the internet! And all of a sudden it's none of that, it's the cloud! What are you talking about?!?

Ellison was correct that the metaphorical cloud consisted of databases and operating systems and memory and microprocessors. But – and that’s what he missed – they were architected differently.

That didn’t prevent Ellison – three years later – from claiming that he had in fact invented the cloud. Nevertheless, Oracle Cloud Platform only launched in 2016. By then, Amazon was well entrenched as the clear leader of the Cloud era.

Oracle Cloud

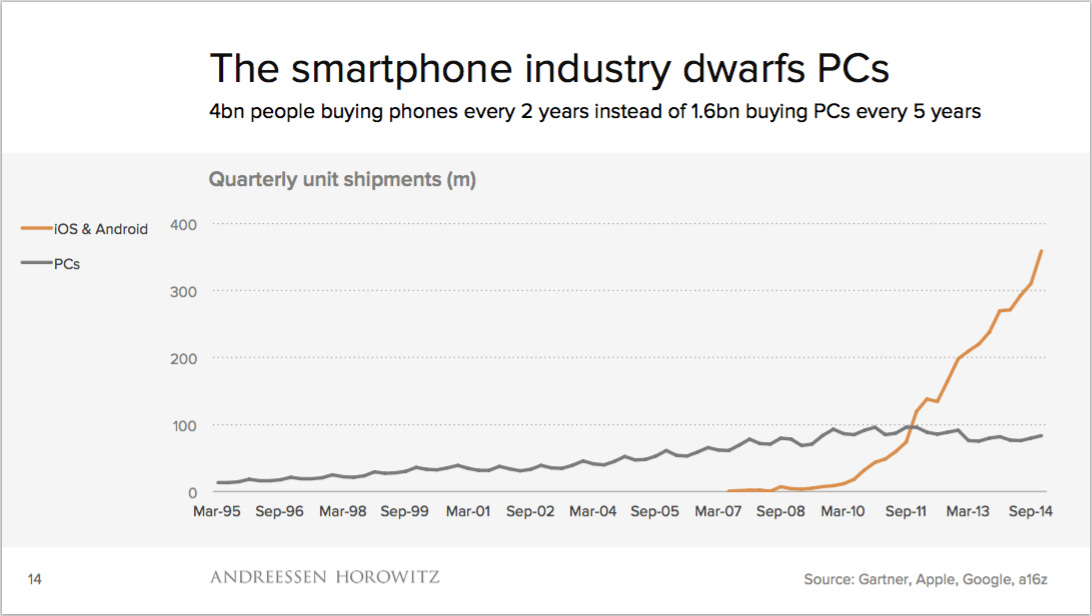

Despite missing mobile, Microsoft still owned Windows, the dominant operating system for PCs; it’s just that mobile phones dwarfed the personal computers, eclipsing Microsoft’s relevance.

Similarly, Oracle is still the leading Relational Database vendor today. It’s just that – with the rise of NoSQL – relational databases are only a segment of the overall database market. That market itself only represents a fraction of the Platform-as-a-Service market, which ballooned throughout the 2010s Mobile and Cloud golden years. Oracle failed to capture a meaningful stake.

During the last phase of disruption, it becomes clear that the new thing in tech – which the incumbent had once dismissed – dethroned the previous paradigm. Having lost the new market created by the disruptor, the incumbent resorts to defending its existing market share.

Many software systems – written in the 1980’s, 1990’s and early 2000’s – are tightly coupled to Oracle Databases. Ellison was mocked when he insisted in 2015 that “transition to the new era of utility computing is still slow”; of course the transition was already in full force for cloud-native companies – such as Uber or Airbnb – born in the age of mobile, but it was indeed slow for Oracle’s traditional customers. Mature companies, with significant IT infrastructure footprint running on-premise. Those who were still asking themselves whether they should join the cloud revolution, and whether it would be worth the risks. Under the Crossing The Chasm model, they are referred to as ‘late majority’ or even ‘laggards’. Their relief came at Oracle OpenWorld 2017, when Oracle unveiled its autonomous database cloud service. The backward compatibility allowed existing customers – those running legacy software built on top of Oracle Database – to make a smoother migration to the cloud, reaping the benefits of auto-scaling and the consumption-based pricing, with less risk.

Steve Ballmer’s strategic mistake was prioritizing Windows, imposing a strategy-tax on Office, instead of making it available on any operating system; Oracle initially made that very same mistake. Oracle Database-as-a-Service was only available on Oracle Cloud, which customers were hesitant to choose over one of the leading cloud providers – AWS, Azure, or GCP. Oracle Database was paying the same type of strategy-tax as Microsoft Office. A few months back, I called it the Platform Hang-Up. Oracle did correct its course in 2023, working closely with the major hyperscalers to offer Oracle Database in Azure, GCP, and AWS. This Platform-as-a-Service offering turned out to be highly successful. Oracle has been reporting triple-digit growth for its MultiCloud segment (albeit from a relatively small base).

Funny as the ongoing Larry Ellison comments about being one of the world’s largest cloud infrastructure companies may have been, Oracle did succeed in carving out a growing segment of the market. I doubt that new companies writing new software systems choose Oracle Database as part of their stack – I’d be surprised if OpenAI is using it, for example; yet there was still money to be made providing a hosted Oracle Database to the late majority, on the cloud provider of their choosing.

AWS and the Winner’s Curse

Here is something Warren Buffett said in 2016, after Amazon had revealed how much money AWS was making:

That's incredible because [Jeff Bezos] developed [AWS] over a six or seven year period, and everybody else sat and watched. and I mean here was a guy that was a business genius, and he's coming on with something big, and the world, his competitors to a large extent, just sort of ignored him. I mean they gave him a lead time which was very very dramatic. I actually sat next to him at a birthday party and he told me how surprised he was that he didn't get more reaction quicker.

You don’t want to give someone like Jeff Bezos seven years of a head start, Buffett said in another interview. The reason that Amazon enjoyed this surprisingly long period of low competition was probably The Winner’s Curse, which distorted the strategies employed by IBM and Oracle. Competition intensified once Amazon shocked the industry back in 2015, by breaking out AWS financial numbers, and unveiling how tremendously profitable its cloud services were.

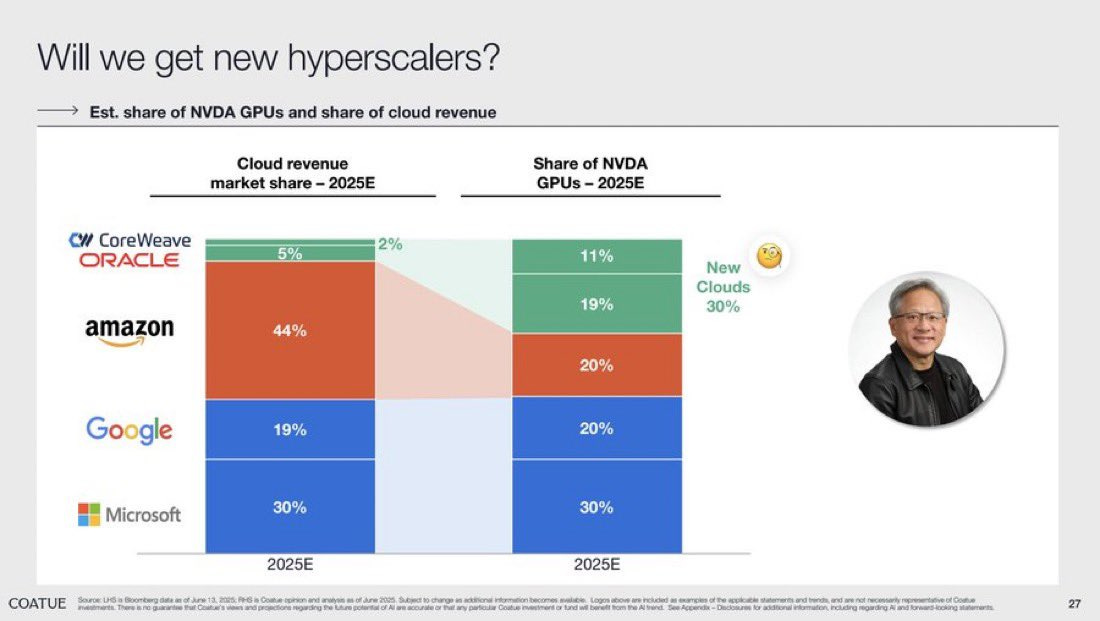

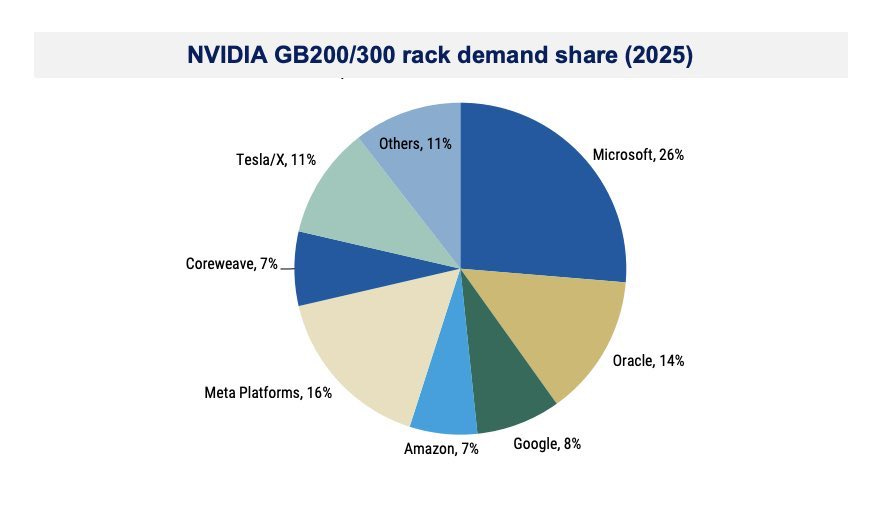

The fascinating conclusion of Thompson’s recent article is that Amazon today might suffer from The Winner’s Curse with regard to the next paradigm shift: AI. Amazon’s strategy assumes that its dominance of the Cloud would extend to AI, and thus it is prioritizing its own custom AI-accelerator chips: Trainium and Inferentia. That’s probably also why Amazon is under-deploying leading edge Nvidia solutions.

To paraphrase Ellison’s 2003 quote, one might think that Amazon’s global-scale data centers provide the ideal low-cost high-performance infrastructure for AI computing. But what if the age of AI requires a fundamentally new architecture to be designed and rebuilt from the ground up? What if Nvidia chips – in which Amazon is underinvesting – end up being the critical linchpin for “AI computing”?

That is exactly the bet that Oracle is currently making. Go back to the graphs above and see how much they’re investing in Nvidia products! They probably make a great partner for Nvidia, given that Oracle – unlike Amazon – is not designing its own AI chip. Could Oracle turn the tables (database-pun intended!), and ride the AI wave to bypass Amazon?

To be clear, at this point I am not worried about Amazon just yet, and I still own shares (full disclosure!) I also maintain a healthy skepticism toward Oracle, given Larry Ellison’s record of overpromising and underdelivering.

The big news around Oracle this week mostly made me think of AT&T, the company that jumped on the iPhone wagon and volunteered to pick up the tab for the huge infrastructure build-out it required. Yet, it could hardly capture any of the value and its stock performed poorly. Similarly, Oracle is hitching itself to OpenAI and Nvidia – signing up for huge CapEx spending – while its ability to capture value remains unclear.

While Oracle’s AI aspirations might end up the same way as its Network Computer ambitions did, it is still a fascinating scenario to consider, and one that definitely requires monitoring. Only the paranoid survive.

The above is for educational purposes only; not investment advice. I am not an investment advisor, these are just my opinions and thoughts.

I love your writing — you’re incredibly talented, and I always look forward to seeing what you’ll share next.

Fascinating