Yahoo, OpenAI, and Bubble Mechanics

How the ever-rising expectations of the dot-com euphoria pushed Yahoo into unsustainable revenue channels, and how something similar might play out with AI

The Yahoo Markets Hypothesis

“Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web” – a website index that was renamed Yahoo! in 1994 – was the first demand-aggregation business on the internet. Nobody called it an aggregator, because it would still take two decades for Ben Thompson to come up with Aggregation Theory; it was still, however, probably the first case that demonstrated it: hundreds of millions of internet users flocked to Yahoo as the entry point for the web. As a result, companies lined up to partner with Yahoo, and have their websites linked from yahoo.com.

As the dot-com euphoria was building up, an interesting phenomenon emerged; tell me this doesn’t sound familiar:

As Yahoo’s popularity surged in 1996, 1997, and 1998, other Internet startups—dot-coms, everyone called them—discovered an incredible reality: Just by announcing a partnership with Yahoo or its rival, America Online, the dot-com’s stock price would shoot through the roof. For example, a company called Individual Investor Online announced it would supply content for Yahoo Finance in August 1998. Its stock spiked 36 percent that same day.

I was reminded of this incredible quote – from the excellent book “Marissa Mayer and the Fight to Save Yahoo!” – after Oracle’s stock surged over 40% on a single day last month; the reason turned out to be a deal to rent GPUs – that Oracle still doesn’t have – to OpenAI (see: Oracle, Amazon, and the Winner’s Curse).

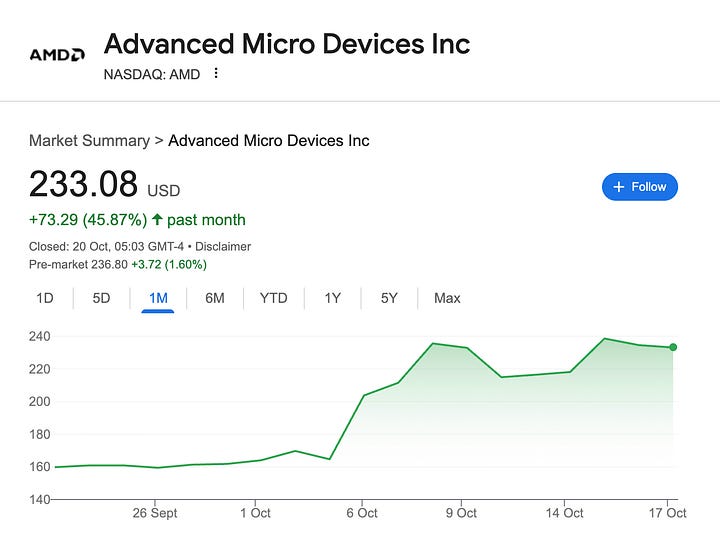

Since then, a corpus of additional OpenAI partnerships was added to the market’s collective context window; from semiconductor companies such as AMD (which stock surged more than 34%), Broadcom (9%), and NVidia (4%); through e-commerce players such as Etsy (spiking 16% on news of ChatGPT integration), Shopify (8%), and Walmart (5%, hitting all-time-high), as well as SaaS companies like Figma (initially rising 16.4% following a ChatGPT integration announcement), Coursera (3.3%), HubSpot (2.6%) and Salesforce (2.3%)1.

You don’t need a frontier reasoning model to identify the pattern here!

Now, I don’t want to get too cynical here. AI is the next major tech paradigm shift, OpenAI is commanding the demand of 800M weekly users2, and it makes sense for them to leverage this position into shaping a complete ecosystem around its product. They are supporting GPU suppliers as an alternative to NVidia, introducing commerce as a potential monetization engine, and trying to make ChatGPT into an operating system. All smart strategic moves. That’s how value is captured. I get it.

I also get why investors are excited about the prospects of businesses taking part in the economic activities of this new frontier. Totally reasonable.

But, like, also, kind of hard to just brush off the fact that OpenAI has the ability to boost stock prices by virtue of issuing a press release? Matt Levine recently commented, “I am always impressed when tech people with this ability to move markets get any tech work done. OpenAI still seems to be building a lot of AI products; if I were them I’d just be day-trading Shopify stock.”

The same kind of dissonance appeared in the 1990’s-Yahoo; yes, they kept on building and launching a lot of web products, but in parallel – facing an immense pressure to continuously demonstrate rapid growth – Yahoo couldn’t help but capitalize on its magical market-moving abilities. Again from “The Fight To Save Yahoo”:

Yahoo executives, particularly its chief dealmaker, Ellen Siminoff, quickly realized the company could profit from the phenomenon. Yahoo developed a lucrative business based on squeezing startups for all they were worth.

Siminoff or one of her lieutenants would field a call from a well-funded startup asking to become Yahoo’s premier bookseller, online travel agency, or music seller. Siminoff would say, Sure, but it’s going to cost you. The startup would say, How much? Siminoff would say, How much do you have?

The answer was “A lot.”

If only Matt Levine had been writing Money Stuff back in the nineties! We could have enjoyed his sarcastic takes, wondering why the value of Individual Investors Online – a print magazine that just recently launched a website and added the word “Online” to its name, and 90% of its revenue was still generated by selling printed(!) magazines – should increase by 36% just because the company is going to host, in Yahoo! Finance, two investor calls every month.

Levine would have potentially come up with a “Yahoo Markets Hypothesis”, in the spirit of his 2021 “Elon Markets Hypothesis”, which determined that “the way finance works now is that things are valuable not based on their cash flows but on their proximity to Elon Musk.” Similarly, the way finance worked in 1999 was that things were valuable based on their proximity to Yahoo, and on being linked from the yahoo.com web portal. “You don’t need economics anymore, you need memes, I’m so sorry,” Levine concluded.

This Time Is Different: Railroads and Internet Portals

At the beginning of the year,

wrote a fantastic post about the underlying mechanics of a technological bubble:Simplistically, money chases high returns. This is intuitive. When an investor makes an extremely high return on capital, capital chases high returns into the space until returns on that capital diminish. This is a fundamental tenant of capitalism.

Usually, there is a correction mechanism. When the supply of capital is too high, the supply and demand of the underlying investment crosses, and returns plummet in the space. Now, there’s another consideration: from time to time, this cycle breaks with a short-term feedback loop, and that is often called a bubble [...] If the world is going to change by introducing a “new technology,” such as railroads, the internet, or AI, it makes sense that there will likely be a massive need for infrastructure. Returns on capital are typically super high initially, and when there are high returns on capital, capital (money) will chase those returns and keep investing in that asset class until the returns collapse. Since there is a vast new capital stock to build, this often takes years to deploy.

[...] As new technology ramps, capital rushes in, and technology that supplies the demand often improves. At some point, the shortage of whatever precious resource is needed becomes a glut.

However, this is how cycles work in a microeconomic way, yet sometimes, a cycle becomes “different this time” [...]

The key difference is an external feedback loop that almost instantly marks up other tangential assets. This … move marks quickly and justifies even more investment. A rapid return on capital will convince early investors that the correct answer is to bet again. Often, the craziest capital cycles had a meaningful feedback loop.

While O’Laughlin mentioned some other examples, Yahoo and the dot-coms perfectly fit into this pattern: the surge in stock prices following a Yahoo deal announcement created the feedback loop that unleashed a “this time is different” cycle. O’Laughlin described another fascinating examples from the railroad era:

The key meme of this period was “territorial development.” Railroads were a transformational network technology. They were 90% cheaper than horses and wagons and enabled new business models based on trade and regionalization. The story goes like this.

Railroads create value by being built. If a railroad is built in a new territory, the land values along the route increase, new towns spring up, and agriculture and industry follow […] This was a powerful feedback loop.

As soon as a railroad announced a plan, speculators would buy land along the proposed route. This would increase the land’s value, which proved the “development thesis.” As more money piled in, the land would be bought before the railroad was even announced, creating waves of booms and busts in speculation.

Sounds familiar?

Announcing a new dot-com startup to be featured in Yahoo’s portal, was akin to announcing that the train was coming to a new town in the 19th century, creating an immediate increase in the price of land.

The vast majority of dot-com startups were far from being profitable. Their money was raised from Venture Capital. There was no good reason to spend much of it on Yahoo’s display advertising – which weren’t highly effective – except for one compelling incentive: they could get Yahoo to announce a partnership, which would send the particular dot-com’s stock surging.

The elevated stock prices would translate into VC profits, which could be reinvested in funding new dot-com startups; the startups could funnel the capital to Yahoo – in exchange for advertising, and more importantly: a partnership announcement – and enjoy the stock price surging. And so on and so forth. If you’re thinking about Web3 or meme-coins – yes, it’s essentially a similar mechanism.

In 1998, venture capitalists invested $22.7B in startups, mostly dot-coms. The amount more than doubled in 1999, to $56.9B. That’s a lot of money to spend on advertising – especially considering algorithmic advertising, the kind that allows ROI measurements, wasn’t invented yet. But the money was spent by well-funded startups, pursuing a Yahoo deal announcement that could send their stock soaring. “The Battle To Save Yahoo” dives into what happens when the Yahoo train was rolling into a new station:

In July 1999, a company called Drugstore.com was preparing to go public. In terms of revenues and profits, it was a small business. In fact, it was losing a lot of money. In the first quarter of 1999, it had sales of $652,000 and losses of $10.2 million. The next quarter, sales reached $3.5 million, but losses steepened to $18.8 million. The company said it had only 168,000 paying customers. And yet, Drugstore.com went ahead with its plans to go public. Investment bankers at Morgan Stanley Dean Witter advised the company to price its shares between $9 and $11 [...] Drugstore.com went public and shares traded all the way up to $69 per share before settling at $54.25. The company planned to go public with a market cap of $680 million. It finished the day with a market value of $2.1 billion.

One reason for the spike: In March, Drugstore.com had announced a major advertising partnership with Yahoo and a few other portals. Drugstore.com would be Yahoo’s premier online pharmacy partner. For the privilege, Drugstore.com paid Yahoo and the other portals $25 million. No one much cared that Drugstore.com had only $38 million in the bank and was blowing it all on just a couple marketing deals—it had a deal with Yahoo.

Not investment advice, but if the stock market is willing to give you a $2B valuation, just because Yahoo mentioned your name, and took $25M in exchange – it’s probably a good deal and you should take it. And investors should probably give you the $25M to pay Yahoo, and make their stocks worth $2B. But it’s obvious who was the real king in this story: The one with the golden touch, who can decide which dot-com stock would be spiking, by virtue of issuing a press release, and adding an html reference on its web page. Yahoo.

The ChatGPT Markets Hypothesis

The problem – which had yet to show any signs in 1999 – was that Yahoo’s banner ads weren’t particularly effective. Click rates were miniscule. The dot-coms couldn’t generate enough traffic to build viable businesses, ones that would continue advertising on Yahoo. It would be a few more years before Google and Facebook figure out how to close the loop – from impression through click to an actual transaction – and utilize the digital nature of the web into building the ultimate marketer’s dream. Alas, companies such as drugstore.com did not have access to such ROI-based tools; its losses topped $100M in 2001, and its stock price completed a 99% drop from its IPO day, to less than $1.

The folks at Yahoo weren’t stupid; they knew that extorting dot-coms for their VC money wasn’t going to be a sustainable business. They knew that, in parallel, they would have to build an advertising program based on delivering actual value to well established companies. Under immense pressure from Wall Street, however, Yahoo was forced to do whatever it took to keep posting strong financial numbers. Former sales executive Jeremy Ring explained in his book, “We Were Yahoo!”:

A third-grader in our position would have known the bust was approaching. Unfortunately, no one was in our position. Individuals nationwide continued to spend money that was essentially imaginary [...] Several of my colleagues and I were highly pessimistic privately, even if our public facade was quite the opposite. [...]

I had been warning for years that we needed to focus less attention on closing big deals with start-up internet companies and focus more on smaller deals that would grow into larger programs over time with major companies such as Target, Wal-Mart, Pepsi, and other traditional advertising spenders. Unfortunately, being the most public of public companies didn’t allow us the luxury. The demands of Wall Street mandated that, through hell or high water, we hit and exceed our quarterly numbers. The pressure was staggering. If Yahoo had ever missed its quarterly numbers, there was a real chance that we could cause an entire market crash, ensuring that millions of people around the world would lose their life savings. We lived with this pressure daily, and it’s what nearly occurred when the numbers were missed–for the first time in twenty-one quarters.

The clock finally hit twelve in September of 2000, and everything turned into pumpkin and mice. drugstore.com wasn’t an outlier; the entire cohort of dot-com startups, that surfed the waves of the world wide web euphoria on their way to the public markets, was going bust. No new vintage of dot-com startups was coming, as retail investors were no longer bidding up Yahoo-linked dot-com stocks, and VC capital was drying out. The alchemy play has run its course.

During her first earnings call as Yahoo CFO, Susan Decker felt obligated to disclose the level of Yahoo’s exposure to dot-coms. Over 50% of Yahoo revenue, she told investors, came from dot-com companies. Yahoo stock crashed to a market cap of $5B, down more than 95% from its $120B valuation at the beginning of 2000.

Is there a lesson here concerning OpenAI? I am obviously not claiming that they are deliberately charging Walmart or Figma for a stock price boost. It is unlikely that anything of this sort is happening right now. Moreover, OpenAI is not even publicly traded (yet), thus it does not experience the kind of “hit or exceed the quarterly numbers through hell or high water” pressure that Yahoo was under.

Consider the following, however: OpenAI is on a mission to build AGI. Or superintelligence / digital god / whatever you want to call it; the point is, it’s going to cost a tremendous amount of money. OpenAI recently announced a series of deals, putting them on the hook for — as per The Financial Times — spending over a trillion dollars within the next five years. OpenAI does not have a trillion dollars; according to the same FT article, it is currently on a $13B revenue run-rate, and yet — The Information recently reported — expects to burn $8.5B of cash this year.

Could such an extreme level of expectations create the kind of staggering pressure that Yahoo’s salespeople experienced in 1999? Just like Yahoo was the face of the dot-com era, ChatGPT is the brand with by-far the largest mind share. OpenAI, in most people’s mind, is providing the entry point for AI. Failure to meet its obligations might cause a serious panic. I imagine somebody at OpenAI must be thinking about this at least once a day.

OpenAI, which started as a non-profit research lab, has already proven its willingness for pragmatism (and rightly so, in my opinion): taking an investment from Microsoft, attempting to convert to a standard for-profit company, and recently building an ad business, and also – hmm, well - porn (incidentally, sex-related content just happened to be the biggest source of traffic back in Yahoo’s days, according to Jeremy Ring’s book).

Combine all that with the fact that – as we have repeatedly witnessed in recent weeks – OpenAI has the ability to move stocks, and you can imagine a scenario where, desperate to stay on the treadmill, OpenAI may look to monetize its market moving ability. That wasn’t Yahoo’s original plan either, but this is what happens when things get too crazy.

There will probably be signs. You can imagine the meme-stock folks starting to bid up stocks like Uber or DoorDash in anticipation of an upcoming announcement about a ChatGPT integration. This will establish the kind of crazy feedback loop that Yahoo had leveraged, and that OpenAI might resort to taking advantage of, by continuously partnering with, how shall we put it – far less established businesses than AMD and Spotify. I’m thinking of crypto coins, quantum stocks, or whatever meme-y corner of the market could still pull in a lot of cash from speculative investors quickly. This is just me speculating! I’m not accusing OpenAI of anything. Just painting a picture of how an extreme bubble scenario could play out over the next few years. Even though the AI bubble has already become the talk of the town recently, it’s possible we have not seen anything yet.

Things can get much spicier from here. Or not; maybe this time is different.

The above is for educational purposes only; not investment advice. I am not an investment advisor, these are just my opinions and thoughts.

Interestingly enough, stocks of TripAdvisor and Expedia were up ~7% initially on the news, but eventually went down. Spotify did not catch a significant tailwind either, despite being included on the ChatGPT integration announcement. This is still a working theory.