Is Lyft In Denial About Robotaxis?

Lyft doesn't seem paranoid about self-driving robotaxis. Latest CEO comments echo Steve Ballmer's iPhone-era vibes.

I don’t think the idea of a driver being replaced by a robot is a very likely thing. In fact, I think it’s zero likelihood in any reasonable time frame.

- Lyft CEO David Risher, November 2025

Inflection Points

Imagine you’re a CEO, running a well-established company, when a new technology emerges. As jagged and immature and unpolished as it may be, the new thing might, at some hard-to-predict point in the future, pose a threat to your business.

Your response can generally go in one of two main directions:

Hit the panic button. Clear your schedule. Your top priority from now on is figuring out how to adapt and make it to the other side of the storm.

Continue as planned. Dismiss the threat with “yes the new tech is incredible, but” type of arguments: explain how the new thing is rough around the edges, too expensive, underperforming, and customers don’t even want it. Focus on your core business instead.

This is basically the innovator’s dilemma; the brilliant insight made by Prof. Christensen was that – as opposed to the popular narrative – successful companies do not fail because they got fat and lazy (they can, in the absence of a disruptive change, remain successful while being fat and lazy); disruption theory basically refuted the ‘stupid manager’ hypothesis, and showed that companies often fail because a thorough analysis favors approach #2, which is more grounded in existing numbers. It is only in hindsight that approach #1 seems like the right choice. We have talked about it several times over by now, starting with the first post.

Andy Grove, the late and legendary Intel CEO, had identified an adjacent phenomenon. A couple of years before meeting Prof. Christensen and declaring his work “the most important business book of the decade,” Grove had famously published Only The Paranoid Survive. Though he didn’t introduce a phrase as catchy as disruption – which the book referred to as “10x changes” or “strategic inflection points” – Grove described another reason CEOs opt into option #2, keeping business as usual in the face of disruption: their emotions.

From Only The Paranoid Survive:

Businesspeople are not just managers; they are also human. They have emotions, and a lot of their emotions are tied up in the identity and well-being of their business.

If you are a senior manager, you probably got to where you are because you have devoted a large portion of your life to your trade, to your industry and to your company. In many instances, your personal identity is inseparable from your lifework. So, when your business gets into serious difficulties, in spite of the best attempts of business schools and management training courses to make you a rational analyzer of data, objective analysis will take a second seat to personal and emotional reactions almost every time.

[...] A manager in a business that’s undergoing a strategic inflection point is likely to experience a variation of the well-known stages of what individuals go through when dealing with a serious loss. This is not surprising, because the early stages of a strategic inflection point are fraught with loss—loss of your company’s preeminence in the industry, of its identity, of a sense of control of your company’s destiny, of job security, and, perhaps the most wrenching, the loss of being affiliated with a winner.

[...] Denial is prevalent in the early stages of almost every example of a strategic inflection point I can think of. During Intel’s memory situation1, I remember thinking, “If we had just started our development of the 16K memory chip earlier, the Japanese wouldn’t have made any headway.”

[...] Senior managers got to where they are by having been good at what they do. And over time they have learned to lead with their strengths. So it’s not surprising that they will keep implementing the same strategic and tactical moves that worked for them during the course of their careers—especially during their “championship season.”

I call this phenomenon the inertia of success. It is extremely dangerous and it can reinforce denial.

When the environment changes in such a way as to render the old skills and strengths less relevant, we almost instinctively cling to our past. We refuse to acknowledge changes around us, almost like a child who doesn’t like what he’s seeing so he closes his eyes and counts to 100 and figures that what bothered him will go away [...]

One of the most famous examples of such denial is Steve Ballmer’s colorful response to the 2007 iPhone announcement:

<laughter> $500 fully subsidized with a plan?

I would say that is the most expensive phone in the world. And it doesn’t appeal to business customers because it doesn’t have a keyboard, which makes it not a very good email machine. Now, it may sell very well or not.

We have our strategy, we’ve got great Windows Mobile devices in the market today. You can get a Motorola Q phone now for $99. It’s a very capable machine, it’ll do music, it’ll do internet, it’ll do email, it’ll do instant messaging. So I kind of look at that and I say, well, I like our strategy. I like it a lot.

[...] Right now we’re selling millions and millions and millions of phones a year. Apple is selling zero phones a year. In six months they’ll have the most expensive phone, by far ever, in the marketplace, and let’s see how the competition goes.

Needless to say, that competition didn’t go very well for Microsoft; it kept making phones that were essentially a miniaturized version of Windows, while the iPhone was taking over the phone market and disrupting the PC. Part of the reason was, probably, that even though Ballmer deserves a lot of the credit for the success of Microsoft’s enterprise business during the 1990s, he was a human being. He had emotions. He could not come to terms with Windows losing its dominance over the computer industry; instead, he closed his eyes and hoped that the iPhone would simply go away.

Lyft’s Denial

The exact sort of inflection-point denial might be repeating itself at Lyft – from Fortune last month:

Don’t expect to see autonomous self-driving cars in widespread use anytime soon, according to Lyft CEO David Risher. The technology doesn’t work yet, government regulators aren’t ready, and consumers don’t like them, he says.

That’s a surprising opinion, given that he aired it in a conversation at Web Summit in Lisbon last week, where 71,000 attendees seemed to be mostly convinced that AI will be able to solve almost any future problem.

Reality is going to get in the way, Risher told Fortune.

“That will be the case for years and years and years to come,” he said. The [car manufacturers] aren’t entirely ready. The technology isn’t entirely ready for fog or snow or heavy rain or whatever it is. People, riders aren’t necessarily excited about it [and] regulators aren’t necessarily enthusiastic about it in every place,” he said.

That’s going to make the rollout of self-driving slow. Risher said he would be surprised if 10% of Lyft’s business came from self-driving vehicles by 2030.

He thinks most people are wary of self-driving cars and prefer a human at the wheel. “Customers won’t demand it. They’ll just say, I don’t want to get in a self-driving car.”

Furthermore, the economics of self-driving are less appealing than most people think. At first glance, getting rid of all your drivers seems like an opportunity for ride-hailing apps to reduce costs while having a fleet of cars available that can respond to any call, for any ride, at any time—because driverless cars never need to sleep.

But Risher points out that a fleet of self-driving cars quickly becomes an expensive asset-depreciation issue. Every night, when the human customers are asleep, the fleet will sit largely unused, its value literally rusting away. All the maintenance, cleaning, and refueling costs would be on the company, and not the drivers. And self-driving cars aren’t cheap. “Today, these cost maybe $250,000 to $300,000, a very expensive product, whereas a Prius or Corolla is maybe $30,000 or $40,000.”

On that basis, it’s far more efficient for ride-hailing companies to not own cars and to instead rent them from individual drivers on an as-needed basis.

To summarize Lyft CEO David Risher’s main arguments, there is no serious threat of Lyft being disrupted in the near future by autonomous robotaxis, because they:

1. Cost a lot of money

2. Do not support some use cases (“fog or snow or heavy rain or whatever it is”)

3. Aren’t appealing to customers

4. Aren’t nearly as widespread as ride-hailing apps

5. Raise a lot of regulatory concerns

I couldn’t help but notice how well this emulates Steve Ballmer’s iPhone reaction; with the exception of the regulatory angle, these were the same exact arguments used to dismiss the iPhone as a threat:

1. Too expensive (“$500 fully subsidized with a plan”)

2. Did not support some use cases, such as writing emails

3. Was not appealing to business customers

4. Microsoft was already selling many millions of phones every year

These are the typical arguments used by incumbents, probably as a defense mechanism, to convince themselves that their core business isn’t in danger. In the previous post I pointed out how Wix – still founder-led – is taking the opposite approach, but the stock might have been better off in the short term, had the management presented similar arguments about vibe-coding, rather than leaning into it.

Reality, however, might break through Lyft’s denial sooner than Risher claims.

Winter Is Coming

The current state of Waymo, which currently leads the robotaxi race, may be enough to refute Risher’s arguments:

1. Waymo was able to achieve a 90% cost reduction since 2009, according to FD. Its 6th generation vehicles (already being spotted in the wild!) are expected to cost between $60,000-$80,000 apiece. While it is double the price of “a Prius or Corolla”, it’s far less than the 8x mentioned by Risher ($250k-$300k).

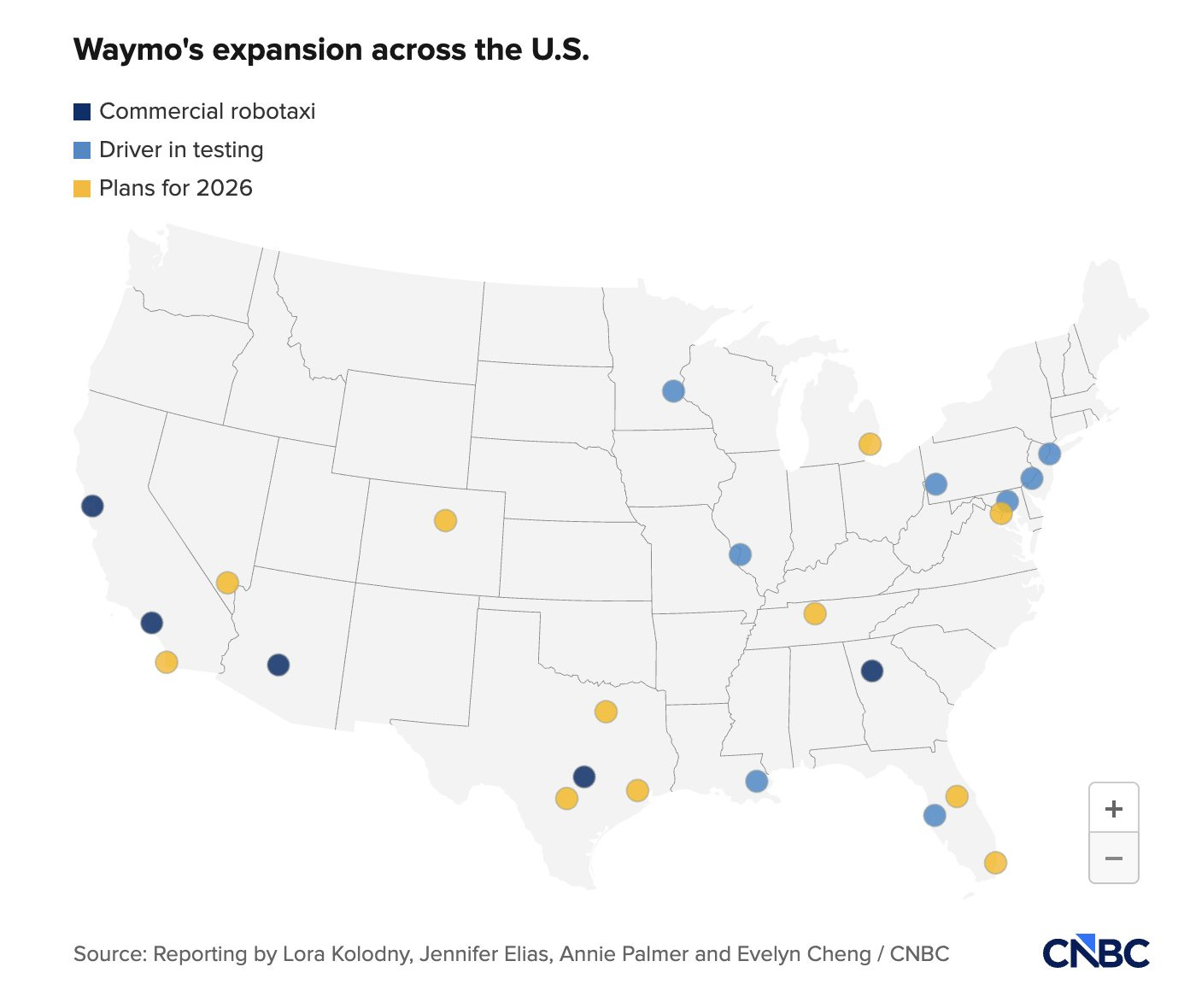

2. In preparation for its 2026 Detroit debut, the first geography with regular snow, Waymo has already reported testing in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and Buffalo, New York. As for fog, well, Risher has probably noticed all the Waymos driving through the San Francisco fog by now2.

3. Customers definitely do want to get into self-driving cars; when I visited San Francisco last summer, I realized that my friends would either take Waymo or drive; definitely not Uber though, since they didn’t want to ride in a random stranger’s car. This seems to represent the general trend – from Waymo Surge (by Mostly Borrowed Ideas ):

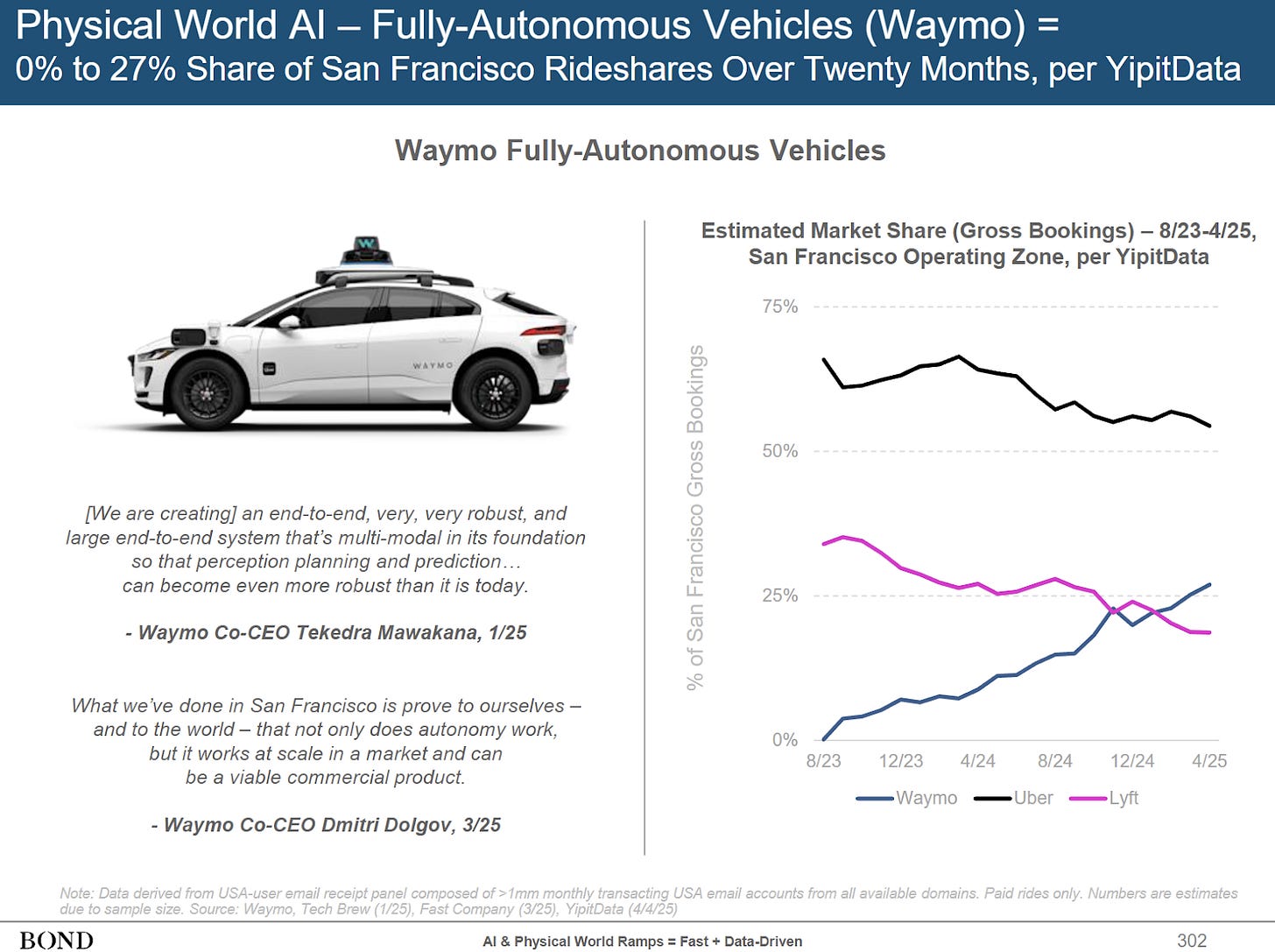

In April 2025, Bond Capital cited Yipit data to show Waymo went from 0% market share to surpass Lyft’s market share and reach 27% in just 20 months in Waymo’s San Francisco operating zone. Remember, this was back in April when Waymo was doing 250k rides per week. Since current weekly ride is ~80% higher, Waymo may have continued to gain market share.

4. Waymo has already announced 25 key markets in which it is going to operate by the end of 2026, and the growth seems exponential. And to go back to the previous point: Waymo only needed 20 months to surpass Lyft in its first market, and could probably do it faster in future ones, as its technology and operations mature.

Moreover, while Waymo is currently ahead, it certainly isn’t the only car on the road. Elon Musk’s promise of “fully autonomous by next year” — which he has been making for almost a decade now — may finally be happening at Tesla. Amazon’s Zoox is already testing its robotaxis, and is expecting to launch the service in 2026. Rivian just announced a push into self-driving. Not to mention the progress made by Chinese robotaxi companies. Even Lyft itself – despite its CEO not being excited over self-driving cars – is partaking, and has announced a partnership with Waymo in Nashville, as well as one with Baidu in London (but how long before they don’t need Lyft anymore).

Considering all of the above, I can’t help but wonder if Lyft’s CEO isn’t simply closing his eyes and counting to 100, hoping that autonomous robotaxis will simply go away. It might make sense, however; what’s even left for Lyft to do about it at this point? They might as well enjoy the party while it still lasts.

Disclosure: not financial advice, this post is for educational and general purposes only and should not be relied upon for investment decisions.

Grove had heroically saved Intel from “the memory situation” in 1980s; more on that in another post.

Waymo did halt service in San Francisco due to a blackout a few days ago, which indicates that further improvements are still required. How long, though, would it keep Lyft relevant for?